Click here to view listing below for Mar 4:3

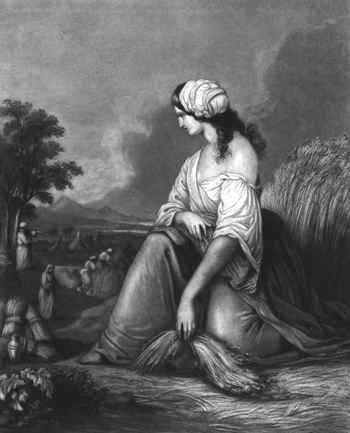

During a famine that raged in Judea in the time of the Judges, a Jewish family of Bethlehem Juda resorted in their need to Moab. The family consisted of Elimelech, Naomi his wife, and their two sons, Mahlon and Chilon. Elimelech died, and his two sons married in the land. The name of the wife of the one was Orpah, and of the other Ruth. The two sons of Naomi died, and left her alone with her two daughters‐in‐law. In her bereaved and lonely state, her heart naturally turned again towards her home. Having heard "how the Lord had visited his people in giving them bread," (Rth 1:6) she determined to return again to Juda. Her daughters resolved to accompany her. After they had proceeded with her some distance, she seemed to feel that they were making too great a sacrifice for her sake, and she besought them to return. She was touched with their devoted affection to her; but determining that her own should be unselfish, she prepared to break the last of those dearest human ties which it makes the heart bleed to break. In language full of gratitude for their love-so cheering to her at such a season-she entreats them to return. "And Naomi said to her two daughters‐in‐law, Go, return each to her mother's house: the Lord deal kindly with you, as ye have dealt with the dead, and with me. The Lord grant that you may find rest each of you in the house of your husband. Then she kissed them: and they lifted up their voices and wept." (Rth 1:8-9.) Still they adhered to their determination to return with her. Yet more earnestly Naomi dissuaded them. "And they lifted up their voice and wept again: and Orpah kissed her mother‐in‐law, but Ruth clave unto her. And she said, Behold, thy sister‐in‐law is gone back unto her people, and unto her gods: return thou after thy sister‐in‐law. And Ruth said, Entreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee: for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God. Where thou diest will I die, and there will I be buried: the Lord do so to me, and more also, if aught but death part thee and me." (Rth 1:14-17.)

In these words is expressed the very soul of clinging affection, and of resolute choice to serve the Lord; and I know not but that the inexpressible charm which is thrown over the whole character and history of Ruth, arises from the fact that her spirit was as gentle as it was firm. However that may be, certain it is that none can read the simple and matchless record of her life without having his heart singularly softened and interested in the character and fortunes of the affectionate Moabitess, and without breathing, as he reads the tale, the involuntary benison, "God bless thee, gentle Ruth."

The incidents of this simple and beautiful story display three distinct types of female character.

It speaks well for the character and consistency of Naomi, that she won so thoroughly the attachment and respect of her daughters‐in‐law. She was one of the people of God in the midst of idolaters. She had been subjected for years to the insidious and fascinating influences of heathen worship. She was far away from the religious privileges without whose constant influence the piety of so many dies. She was straitened and perplexed in circumstances. She had-and in this thing she erred-she had formed intimate connections with the idolaters among whom she lived, and the amiable and affectionate characters of her daughters‐in‐law might naturally make her think well of the false religion in connection with which such characters were formed, or could continue to consist. She had none of the restraints of public opinion, as in her own land, to keep her heart true to her fathers' God. She was surrounded by temptations to conciliate those among whom she dwelt, by adopting their views and joining in their idolatrous ceremonies. And to withstand all this array of adverse influences, she had nothing but a poor, bereaved, almost broken woman's heart. It is difficult to conceive circumstances more trying to the fidelity of the child of God. Yet she seems to have withstood them all. The grace of Israel's God was sufficient for her. Through all her long years of various trial, she did not forget Jerusalem or cease to testify to the power and goodness of the God of Israel. Instead of being overcome by the heathen influences around her, she exerted an influence for the true God over those immediately connected with her. She not only won the personal attachment and respect of her daughters‐in‐law, but her life and character convinced them that the Lord whom she worshipped must indeed be God. It seems to have been by the daily sanctity of her life; by her long and consistent walk as a child of God; by the silent eloquence of a beautiful and holy example, that she impressed her daughters with the conviction that her God was real; that he exerted over her a mighty power; and that she found in him a true, living, and sufficient portion. Very beautiful does this faithful example of Naomi appear in the midst of surrounding idolatry. It was not a far‐blazing, but it was a clear and steady light shining in a dark place. We feel that, in the highest sense, she deserves her name of Naomi, or beauty.

The example of Naomi exemplifies an element of influence in the cause of God, as unobtrusive and gentle as it is mighty. The people of God are now often intimately connected with the world's idolaters. However adverse may be the circumstances in which they are placed against their exerting an influence for their God and Saviour; and however much they may feel that the world's insidious influences tempt them to forgetfulness or denial of their Master; they are not in a situation of so much difficulty, in these respects, as was faithful Naomi. In that position they may, if they are faithful at least, win some gentle Ruth to say, "thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God." (Rth 1:16.) A holy, consistent, and beautiful example of Christian character, is at the same time an argument and an influence for God. It is an argument, because it is a Divine effect which proves its cause Divine. When the men of the world see the true fruits of the spirit, and when these blessed fruits are before them so constantly that their attention and inspection is renewedly forced upon them, they are compelled to confess that the seed of them must be heavenly, and that their growth must be under heavenly light and dew. If they saw the virtues of true Christians only casually and at a distance, they might not be able to discriminate them from the virtues of the world's worshippers. But when they are brought into the immediate presence of the manifested graces of the spirit; when they can watch their blossoming and growth and ripening; when they daily inhale their heavenly fragrance, and are daily cheered and blessed by their holy beauty as by a benediction; then they cannot but discern the difference between these immortal graces and the world's gaudy and perishing virtues. If they have lived intimately for years with the holy children of God, they will not and do not say that there is nothing in the religion of the Saviour; that the fruits of the spirit are no better than the fruits of earthly morality; that the apples of Paradise are no sweeter than those of Sodom. They are convinced by an argument whose premises every day's history has confirmed, and whose conclusion therefore they no longer can deny. Nor is a holy and consistent Christian life less an influence than it is an argument. They who have witnessed these graces, have also felt and shared their power. Such thoughtful regard to their happiness and welfare; such real love; such self‐denial for their sakes; such assiduous and tender ministries in hours of bereavement and reverse, they have never experienced from their worldly friends. Grateful and admiring, they will respect and love the principles of which these are the refreshing and blessed manifestations. Now, what an influence over human minds and hearts is here exerted by the true, steady, life‐long disciple of the Saviour! When this argument has convinced the mind, and this influence touched the heart, is not much of the opposition of man to the claims of Christ already done away? May not the spirit now apply its persuasive influences with more hopes of success? I know that the opposition of the natural heart remains, and that nothing but the grace of God can overcome it. I know that the inner citadel is yet untaken, and gleams and bristles still with the instruments of hostility and defence against God and against his anointed. But the ramparts are broken down; the fortifications are dismantled; the gates are opened; the guards are sleeping; and now that power of Divine grace which might in vain have been brought against the alert and rallied opposition of the natural man, may overcome its slumbering and hesitating and confused defence, and enter in and be welcomed by a willing surrender, and plant there the standard of the cross; while witnessing angels rejoice and sing over one more conquest won for Jesus!

Compare this silent and potent influence of example with that of the preaching of the gospel by the ministry of the word. I would not underrate the preaching of the gospel, because its foolishness is the power of God unto salvation, when the cross of Christ crucified is the theme. But it is then most effective when it has been preceded and seconded by the persuasive and convincing influence of example. But it, of necessity, arouses the opposition of the natural heart. It calls upon the soul for an immediate surrender to Christ. It charges home upon the individual his sin and his condemnation. It immediately suggests all the difficulties and self‐denials of the Christian warfare. With whatever skilfulness or tenderness-with whatever of winning appeal-with whatsoever constraining motives it may be presented and urged; still, if it be faithful, it challenges the soul to this most repulsive work of forsaking the world and sin, and of surrendering itself to God. It comes to him as the tempest which makes him wrap closer around him the cloak of his impenitency. But silent example is the melting sunshine which makes him, of free choice, throw it off. A holy example does not, like the spoken word of the preacher, demand his instant attention to repulsive truth. When he contemplates that example, or the truth of God in it, he seems to do it of his own free choice, and he comes to its consideration without that spirit of opposition and irritation which arises in his mind from having been challenged or entreated to contemplate and receive the truth to which he is opposed. His mind is not thrown into an attitude of cavil or opposition. He is taken when off his guard. There he sees religion in its fruits, not in its demands on him. He sees it in its blessed effects on others, not in its stern and uncompromising requisitions upon himself. He thus becomes unconsciously accustomed to associate it with all that is excellent and pleasant. Conviction steals upon him unawares. He is won to acknowledge the Divine beauty and blessedness of the gospel. Then the preached word may come to his heart in demonstration of the spirit and of power. Then he may not be so utterly indisposed to entertain the question, "Ought I, must I, shall I turn to God?" Tenfold would be the power of the pulpit, if in households and in society, faithful Naomis would compel the world's worshippers to confess, "Our God is not as your God, ourselves being judges." Then when the question was distinctly proposed, "Will you leave all and follow Christ?" there would be, at least on the part of the gentle and true‐hearted Ruths of the world, the fervent declaration accompanied by a solemn oath, "thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God!" (Rth 1:16.)

But the example of the holy consistency of Naomi has detained us too long from the contemplation of the beautiful teachableness, affection, and resolution of Ruth.

It appears that Ruth made a fixed and unalterable choice. That choice she confirmed by a solemn oath: "The Lord do so to me, and more also, if aught but death part thee and me." (Rth 1:17.) She chose God and his people. She chose them without reservation. She chose them under all possible circumstances in which they or she might be placed. She chose all their portion-in life and in death. It was a deliberate choice-made after her sister had come to an opposite determination; made even against the dissuasions which the disinterested affection of Naomi prompted; made against the suggestions of natural affection for home and kindred, and in the face of probable destitution and struggle among strangers, in a strange land. Persuaded of the wisdom of her choice, she was ready in yielding to grace to crucify nature. She had been convinced by the character and conduct, and perhaps the instructions of Naomi, that the God of Israel was the true God. She was therefore determined to serve him, and to take him and his people as her friends and her portion. When her choice was tested, it was deliberately, solemnly, and by oath renewed, and at once acted upon. Such were the circumstances under which her choice was made, and such the comprehensive tenor of her declaration: "Entreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee: for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God. Where thou diest will I die, and there will I be buried: the Lord do so to me, and more also, if aught but death part thee and me." (Rth 1:16-17.)

Now it is in this decisive act of choice on the part of Ruth, that we discern the essential difference between her and her sister Orpah. They may be regarded as the types of two characters to whom the gospel addresses its conclusive claims, and of whom it asks a prompt decision. Orpah and Ruth appear to have been both alike attached to Naomi, and alike convinced that she served the true and living God. Both went on their way to return with her to Judea. Both wept when the mother relinquished them, and bade them return; and both professed their determination to accompany her to her home. But by Orpah, as the result shows, all this was done under the impulse of excited feeling. She seems to have been a person of that quick sensibility which shows all of itself at once and soon passes away, without much real heart and with no strength of will. This seems to be evident by the record of their history, brief as it is. When they wept at Naomi's suggestion that they should remain at home, Orpah kissed her mother‐in‐law, while Ruth only clave to her. Orpah showed, seemingly, the most fervent and affectionate feeling. Hers was a character not uncommon-described in the parable of the sower by the ground which had not much depth of earth, on which the seed soon sprang up promisingly, but withered away in the sun. (Mar 4:3-6.) She was what her name expressed-Orpah, the open mouth-ever ready with the warm kiss of awakened sensibility, and with the earnest protestations of affection. But there was no depth to her character. It was a thin cold soil with a rock underneath. When these sudden gushings of sensibility ceased, then the heart was left empty. They exhausted all that was in it. There was no perennial fountain of feeling. There was no abiding affection, built on a long experience and due appreciation of valuable qualities in her she loved. Especially there was no strength of will, to carry out what reason and conscience told her was wisdom and duty. She was a mere creature of sensibility. It was feeling that induced her to determine to follow Naomi; and feeling which induced her, when she had started upon the journey, to turn back. With the memory of Naomi's example before her, and with the knowledge that her God was the true and mighty God, she yet was daunted when she saw the magnitude and difficulty of the undertaking, and went "back to her people and her gods." Ah! these Orpahs-whom sympathy and affection for their pious friends or pastor induces, with much show of feeling, in a moment of excited sensibility, to enter upon the path of life-we know them! These are they whose apparent zeal and fervour awaken the best hopes of pious friends and anxious pastors, and whose subsequent turning back to their people and their gods causes them deepest pain. "In time of temptation they fall away!" (Luk 8:13.)

How different was the character and conduct of the earnest, deep‐hearted, but gentle Ruth! She too was true to her name-Ruth,-full or satisfied. Hers was not an empty nature, capriciously craving she knew not what. It was full of right views and feelings, and in their possession and exercise she was fully satisfied. She made no greater protestations, and she showed less outward appearances of affection for her mother‐in‐law than Orpah. She made no boast of her firm and unshaken resolution to share her mother's fortunes and serve her mother's God. When Naomi, in view of the trials which they would meet with, urged them to return, Orpah kissed her mother, but Ruth clave unto her. Orpah kissed her-but she left her. Ruth did not kiss her-but she clave to her. In that expressive clinging to her mother, we may perceive the very character of an humble, true, and steadfast love. "Orpah kissed her, but Ruth clave unto her." (Rth 1:14.) The one was as the leafy branch, which the wind dashes a moment against the oak, whose rustling all may hear and whose waving all may see. The other was as the humble, clinging ivy, which almost unseen embeds itself in the trunk, and silently twines itself around it with a grasp which may not be unloosed but with its life. It was not until Naomi had reiterated her request to Ruth to leave her, and enforced it by the example of her sister, that she gave utterance to the fixed purpose of her will, and opened the floodgate to the rich tides of her pent‐up affections. The difficulties of the undertaking, and the persuasions of her mother, which turned back Orpah and overcame her superficial love and her feeble purpose, did but give energy to the decision, and added fervour to the self‐forgetting affections of Ruth's true heart. Then it was that the quiet and unobtrusive strength of her heart and will were forced into expression, and she gave utterance to her love and her devotion to God and his people in words whose simple eloquence never has been-surely never can be-surpassed: "Entreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee: for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God. Where thou diest will I die, and there will I be buried: the Lord do so to me, and more also, if aught but death part thee and me." (Rth 1:16-17.) True‐hearted and faithful Ruths-we know them also! They are steadfastly minded to go with, and, if need be, suffer affliction with the people of God, rather than enjoy the pleasures of sin, which are but for a season. They are the joy of the pastor's heart; the pride of the people of the Lord.

It is in this feature of the character of Ruth-her wise choice and her firm will, made firm through grace by a fervent and constant heart-that we find the most important lesson of her history. The religion of Jesus Christ must be made by each individual the subject of deliberate, unalterable, final choice; and all the influences which it may exert short of this determination avail nothing. This is the matter of choice or rejection. Christ Jesus, the incarnate Son of God, lays down his life for our sins; invites us to accept him as a substituted victim to the penal wrath of God because of our transgression, and offers you pardon, sanctification, salvation. Choose now-this or that? Accept? or not accept? That is the question! It is to be made a matter of choice with us. Howmuchsoever we may talk about it, and inquire, and object, and feel, and hesitate, the question comes back to us, "Accept? or not accept?" I know that we cannot choose without the aid of the Spirit of God, giving us a willing heart to take Christ as our portion. But this truth lies back of the great question-the question which we must settle by free, deliberate, solemn choice, in view of all the present and eternal consequences of our decision-"Accept or not accept?" When we know ourselves to be sinners, and perceive Jesus to be a sufficient Saviour, and the offer of salvation is made to us by him; then let us see to the making of that choice which wisdom and duty, fear and love, heaven and hell alike enjoin; let us see to the making of that grand election, in prayer and dependence upon grace, and God will see to giving us the grace by which it may be done. Though nature reclaim against the purpose, and the sins of the heart rise in opposition, and Satan arm them with tenfold power, let us look to the eternal woe to be shunned; let us look to the constraining motives addressed to our heart and conscience; let us look to the blessings which belong to God's people here; let us look to the bright future of unending rapture; and, above all, let us look to JESUS, the incarnate loveliness, the dear friend, the dying Saviour; let us look to Jesus, and the felicities which gather about him, till our hearts are penetrated with desire, and our will braced up to a heavenly temper which earth and hell cannot break or bend, and then say, with the noble resolution of faithful Ruth, when friends and pastors speak to us of their Lord and their Land, "Whither thou goest I will go; thy people shall be my people; thy God my God; God do so to me and more also if aught but death part thee and me!" (Rth 1:17.)

But the difficulty with multitudes is that they will stop just short of this decisive choice, and therefore gain no blessing. Impressed, perhaps, by the example of some holy Naomi, they have had their minds convinced of the necessity and excellence of the religion of the Saviour, and their affections have been called out toward the people of God, and all their prepossessions and feelings may be in their favour. They may even, under the mere impulses of a convinced mind and a touched heart, have outwardly connected themselves with God's people. Still they have not made it the matter of a deliberate, solemn, unchangeable choice to serve the Lord, and bind themselves to his people in all circumstances and on all occasions; taking them in the whole of their fortunes; "going" only "where they go," in the paths of self‐denial and away from the haunts of worldliness and sin "lodging where they lodge,"-living in quiet and sobriety, far away from the world's noisy dissipations; "dying where they die,"-in the presence of the angels that rejoice to bear them to their home. They have bound themselves by a resolute, free, rejoicing choice, whose record is in heaven, to take Christ as their ALL,-their righteousness, sanctification, and redemption in life, in death, for time and for eternity. When the trial‐time arrives, and the self‐denial and crucifixion of nature's affections is to be made, then it is seen that the choice for God, in view of all possible circumstances, has not been made. They fall away. They walk no more with the people of God. Demas-he was one of these persons-"Demas hath forsaken me," says St. Paul. (2Ti 4:10.) Then does the difference appear between those who have made the choice and those who have not; then, and then only, can we discern the vast difference between the character and position of Orpah and of Ruth. The one may feel drawn towards Bethlehem and God's people, but her choice is with her old people and her gods. The one may weep as she leaves the blessed portion; but still she leaves it.

Those, then, who are in the condition of Orpah, with their understandings satisfied and their hearts interested in the people of God and in the outward services of religion, need not flatter themselves, as they are apt to do, that their portion is already with the saints. Nothing to the purpose has yet been done. A solemn, specific act of consecration, which the will stamps with its seal, which no man or angel can be allowed to break;-this solemn, everlasting covenant with God, never to be broken or forgotten, must be made, or all the preparatory work will be in vain. It is an act of the soul. It is transacted when the soul goes for that purpose into the presence of God, and asks him to gather around it in dread array, to witness and confirm the solemnity, heaven, hell and judgment, and in their presence strikes the eternal compact and utters the irrevocable, eternal oath. It is an act of the silent soul. Every human being to whom the gospel comes is called upon to make a decision. Reader! have you made it? You may fatally postpone, but you cannot avoid that decision. By postponement you make a decision for the present. You go with Orpah. Beware lest, when called upon to make that decision, you for ever destroy the hope of return. Of Orpah we hear no more but this-that she returned to her people and her gods.

The Blue Letter Bible ministry and the BLB Institute hold to the historical, conservative Christian faith, which includes a firm belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. Since the text and audio content provided by BLB represent a range of evangelical traditions, all of the ideas and principles conveyed in the resource materials are not necessarily affirmed, in total, by this ministry.

Loading

Loading

| Interlinear |

| Bibles |

| Cross-Refs |

| Commentaries |

| Dictionaries |

| Miscellaneous |