Click here to view listing below for Jon 4:6

Are Some Books Missing from the Old Testament? – Question 6

In our previous question, we found that neither the Jews, Jesus, nor His apostles accepted the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha as Holy Scripture; there is really no doubt about this. All the evidence, from 200 B.C. onward shows that there was a fixed canon of Old Testament Scripture. This canon did not include the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha. Thus, the Roman Catholic claim, that there was a greater canon in Alexandria, Egypt, than in Palestine, has no historical evidence to support it. Neither was there the need for any council, Jewish or Christian, to meet and determine the extent of the canon.

This being the case, we now look at how the Christian Church from the time of Christ until the present, viewed the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha. What have believers had to say about this issue?

The Roman Catholic Church claims that the status of the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha was not officially settled until the council of Trent in 1545-1563. However, Rome says that Trent merely acknowledged the historical view of the church in its pronouncements with respect to the Old Testament Apocrypha. The common practice was to accept these books as divinely inspired along with the rest of the Old Testament.

Those who argue for the inclusion, or the exclusion, of the Old Testament Apocrypha as part of Holy Scripture often appeal to the testimony of past Christians. Therefore, it will be helpful to know exactly what those in the ancient church had to say about the Old Testament Apocrypha and its relationship to the Hebrew Old Testament. Consequently, we will consider some of the highlights in the history of the church with respect to the inclusion, or exclusion, of the Old Testament Apocrypha as part of Scripture.

In our response to the Roman Catholic claim we will look at the evidence in the following manner. First, we will consider the evidence from the second and third centuries of the Christian era. What statements about the canon do we find? What lists were drawn up of canonical books and what did these lists include?

Next we will look at the evidence from Eastern Christianity from the fourth and fifth century. What did they have to say about the canon? We will then look at the fourth and fifth century views of the canon from Western Christianity. Is their history with the canon the same or different than those in the East?

Our next section will consider the highlights of the history of the canon from the sixth century until the Protestant Reformation. What did the church have to say about the canon during those years?

We will then consider the views of the Protestant Reformers with respect to the canon as well as the Roman Catholic response at the council of Trent. Our final section will examine the various views of the Old Testament canon from the council of Trent until the present. We will then make a number of observations about the evidence we have considered.

It is our intention to present the highlights of the last two thousand years of church history with respect to the subject of the Old Testament canon. We do not intend to be exhaustive. However, we do plan to deal with the major events that have occurred. This should give us an accurate picture of the stance of Christians with regard to the Old Testament canon. In doing so, we will discover that those who claim that the Old Testament Apocrypha has always been part of the Old Testament of the Christian church do not have the historical evidence on their side. On the contrary, we will discover that the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha were added to the Old Testament Scripture for a number of unfortunate reasons and that they have no right to be called Holy Scripture.

The historical evidence can be simply stated as follows:

After the time of the apostles, in the second and third century A.D., canonical lists of the Old Testament Scripture were beginning to be drawn up. During this period of time, the church was largely made up of Gentiles. Their language was not Hebrew, rather it was Greek. Thus, for the most part, they knew the Scriptures in the Greek Old Testament or from translations made from the Greek Old Testament. Though their main language was Greek, we find that the first canonical lists matched up with the Hebrew canon of Scripture. From these first two centuries after the time of Christ, we can note the following evidence.

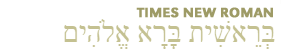

The earliest list of the Old Testament books from a Christian source is from Melito, Bishop of Sardis. We know of this list from the writings of the church historian Eusebius who reproduced it in his writings. According to Eusebius, about the year A.D. 170, Melito wrote a letter to a man named Onesimus. In his letter, Melito states that Onesimus wished to know the number, as well as the order, of the Old Testament books. Melito listed the books of the Old Testament Scripture by their Greek names. He had compiled this list from a trip he made to Palestine. In his letter, Melito stated the following:

When I came to the east and reached the place where these things were preached and done, and learned accurately the books of the Old Testament, I set down the facts and sent them to you. These are their names: the five books of Moses, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua the son of Nun, Judges, Ruth, four books of the Kingdom, two books of Chronicles, the Psalms of David, the Proverbs of Solomon and his wisdom, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Songs, Job, the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, The Twelve in a single book, Daniel, Ezekiel, Ezra.

The reference to the four books of the Kingdom would be First and Second Samuel and First and Second Kings. Ezra was the common way to refer to Ezra-Nehemiah. We also assume that Lamentations was included with Jeremiah. Wisdom was merely a fuller description of the Book of Proverbs ? not the Old Testament Apocryphal book by that name. Among ancient writers, Proverbs was also called “Wisdom.”

This list of Melito includes all the books of the present canon except Esther. However, it is possible that Esther was accidentally omitted seeing that it is often the last book enumerated in ancient lists. This seems to be the case since Melito’s list contained only twenty-one books. The first-century Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus, said the extent of sacred Scripture was twenty-two books. While Josephus does not list the individual books, Melito does. Melito lists all of the traditional Old Testament books of the Hebrew canon except the Book of Esther. Thus, if we count Esther, we would come up with the same number; twenty-two.

While including all of the books of the present Old Testament canon (except Esther) Melito nowhere mentions any of the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha. He is the first person known to describe the specific contents of the Old Testament.

About the time of Melito, another list of Old Testament books was also drawn up. It has been preserved in a manuscript in the library of the Greek Patriarch of Jerusalem. It is known, among other names, as the Byrennios List. The names of the Old Testament books are found in both Greek and Aramaic. This list has twenty-seven books.

In this list, like Melito’s, Lamentations is most-likely included with the Book of Jeremiah. Ezra/Nehemiah is called First and Second Esdras. Though omitted in Melito’s list, the Book of Esther is included in this list. This may give further evidences that Melito’s omission of Esther was an oversight.

Whatever the case may be, the books which are listed are exactly the same as we find in our present Old Testament; they are just divided differently. The number twenty-seven may correspond to the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet, along with the special form that five letters take at the end of words.

Therefore, from the two oldest canonical lists of Old Testament Scripture, we find them in basic agreement as to their contents. The books of the Hebrew canon are all listed, but the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha are not included on either of these first two lists.

Next we come to the list given by the church father Origen. As was true with the Old Testament canon listed by Melito, we also know the view of the canon of Origen from the writings of the church historian Eusebius. This list from Origen, which originally was written as part of a commentary on Psalm 1, can be dated around the year A.D. 230.

Eusebius tells us that Origen said there were twenty-two books in the Old Testament. He listed each of the books in Greek characters and in Hebrew. Though Origen said there were twenty-two books in the Hebrew canon, his list only has twenty-one. The Minor Prophets are omitted. However, this had to have been an oversight since Origen elsewhere cites the Minor Prophets as Scripture. Apart from this omission, the writings correspond exactly to the traditional Hebrew books, as well as to the two previous lists we have just considered.

However, though Origen only accepted the traditional books of the Hebrew canon, he also accepted certain additions to the canonical books. These include the additions to Esther, Daniel, and Jeremiah. Origen, like others in the early church, believed that the Jews had altered some of the contents of the Hebrew text.

While Origen accepted these additions as part of Old Testament Scripture, he does not accept the Old Testament Apocrypha as Scripture. In fact, he says the books of the Maccabees are outside of the canon. Origen makes it clear that the church accepted the same canon which had been handed down by the Jews from earlier times. Nowhere does he state that the church adds or accepts other books to this canon which he listed. Thus, what we find with Origen is the same number of canonical books as in the first two lists, but we also see a willingness to accept additions to certain books.

To sum up, what we learn from each of these three early lists is that the church received and accepted the same canon that was universally accepted by the Jews in the first century. The fact that Origen mentioned the book, or books, of the Maccabees tells us that the church was using other Jewish written works. However, they were not using them as authoritative Scripture. There was a clear distinction between the canon, handed down from the Jews, and these other works.

Consequently, what is clear from the evidence is that for the first three hundred years of the Christian Church, no writer who gave us a canonical list of Old Testament Scripture placed any books on his list which were outside of the Hebrew canon.

If this is the case, then when did these additional books become accepted as part of the Old Testament canon by some members of the church? To answer that question, we will have to look at the testimony of the church fathers from the fourth century and the fifth century.

We will now move to the testimony of the Church Fathers from the fourth century who lived in the Eastern part of the Roman Empire. Their testimony can be simply stated as follows:

As we have seen, the church historian Eusebius preserved the canonical lists of Melito and Origen. He also preserved the list of first century writer Flavius Josephus. Thus, we find that at the beginning of the fourth century, the church was continuing with the same canon that the Jews had handed down and that Jesus and His disciples had accepted.

In A.D. 367, the great defender of orthodox belief, Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, Egypt, wrote an Easter letter that circulated to all the churches in Egypt. In this letter, he stated there were twenty-two books in the Old Testament canon. He connects these twenty-two books with the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet. He has the same books as found in the previous lists with the exception of Esther, which he omits. Like Origen, he adds Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah with the Book of Jeremiah. Lamentations is also added to Jeremiah.

Athanasius made the distinction between these canonical books and the Old Testament Apocrypha. He recognized that works such as Tobit, Judith, Sirach, the Wisdom of Solomon, and Esther were to be read in the churches but were not to be used to establish doctrine. He said:

[They are] not included in the canon, but appointed by the Fathers to be read by those who newly join us, and who wish instruction in the world of godliness.

This is another ancient and powerful testimony that the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha were not considered to be Holy Scripture. However, as we just mentioned, Athanasius mistakenly places Esther with the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha.

Gregory of Nazarinius, the Bishop of Constantinople, also provides us with a canonical list. Like Athanasius, he also links the twenty-two books with the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet. His list is the same as that of Athanasius; twenty-two books, with Esther omitted. Interestingly, unlike Athanasius, he does not include the Letter of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah to the Book of Jeremiah.

Cyril was Bishop of Jerusalem for a time. However, he was persecuted for some of his beliefs and his position was taken away from him. He has given us a canonical list of both testaments. He listed twenty-two books as belonging to the Old Testament. Like Athanasius, he included the letter of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah in the Book of Jeremiah. Unlike Athanasius, he included Esther in his canonical list.

After listing the New Testament canon, he, like Athanasius, notes that there are some other books read in the church which are outside of the canon. Again, like all of the other writers, we find no book of the Old Testament Apocrypha on his list of Holy Scripture.

Epiphanius, Bishop of Salamis, actually gives us three canonical lists. His first list consists of only twenty-one books, omitting Job. However, this seems to have been accidental since Job is found in his other lists. The Book of Jeremiah does not contain any of the additions as is found in the canon of Athanasius.

He also has a list of twenty-two books. In it, he includes Esther in his list. Interestingly, he called attention to the fact of the significance of the number twenty-two. He said, “There are twenty-two works of God during the six days of creation, and the twenty-two generations from Adam to Jacob.”

His third list numbers the Old Testament writings at twenty-seven. After he lists the New Testament canon he mentions Sirach and Wisdom of Solomon as being similar to the Old Testament in their substance. However, he does not consider them as Holy Scripture.

He also recognizes, like Athanasius, that there are two classes of books which are read in the church. He names the second class of books “Apocrypha.”

Amphilocius, Bishop of Iconium, has a canonical list which has twenty-six books. While he omits Esther in his list, he does say that some people do add Esther to the Old Testament. His twenty-six books, plus Esther, are the same books which we find in other lists.

We conclude this section with the Council of Laodicea. The exact date of this meeting is uncertain. It is the first church body that ruled on the canon of both the Old Testament and New Testament Scripture. This council resolved that only books from the Old Testament canon and the New Testament canon should be read in the church. In another resolution it seemed to have adopted a list of twenty-two canonical books for the Old Testament, including Esther. However, we seem to have adopted this resolution, or canon, which was adopted by this council that questioned its authenticity. In some later lists of what this council adopted or resolved, this particular decision is not listed.

To sum up the evidence which we find from the church fathers from the East in the fourth century we discover that all of them held to the exact same canon as did the Jews; a canon of twenty-two books. In fact, with the exception of Amphilocius and one of the lists of Epiphanius, all of the other sources list the books at twenty-two. None of them added any of the extra books of the Old Testament Apocrypha.

However, some of them did believe the additions to certain books as Scripture, in particular, the additions to Jeremiah. Furthermore, as we have seen, there was some doubt about the status of the Book of Esther. Yet, in all of this, there was no adding of other books to the Old Testament canon apart from the books that were handed down from the Jews.

Since this is the case, we may rightly ask the question, “Where and when did these books of the Old Testament Apocrypha become added to Holy Scripture?” To discover this answer, we must look to Western Christianity and the events that developed in that part of the empire. From there, we will discover how certain books were placed with Holy Scripture even though there was no historical evidence whatsoever for their inclusion.

Next we will consider the testimony of the church fathers from the Western part of the Roman Empire. As we will see, their experience with the Old Testament canon is somewhat different than those from the East. It is from the Christian West, that certain books from the Old Testament Apocrypha eventually made their way into Holy Scripture.

In the Western part of the empire, we find no listing of canonical Scripture before the fourth century A.D. When we do begin to see lists, we will discover that the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha were added. These works were added, not because of any serious study of the issue, but rather because of the popular usage these books enjoyed among the rank and file members of the church. The sad history can be summarized as follows:

Hilary was the Bishop of Poitiers. In a commentary which he wrote on the Book of Psalms, he listed the books of the Old Testament. He numbered them at twenty-two. His list included the Book of Esther. However, at the end of his list he noted that some people have a canon of twenty-four books with the addition of Judith and Tobit.

The Cheltenham List, also known as the Mommsen Catalogue, is a Latin list of the books of the Old Testament and the New Testament. The Old Testament contains twenty-four canonical books. However, the twenty-four include First and Second Maccabees, Tobit, and Judith. The way the list calculates these twenty-four books is by combining three of the works of Solomon into one book; Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, and Proverbs.

This seems to be the first time that these books, considered to have been written by Solomon, were counted as only one book. What seems to have happened is that the author of the list wished to accomplish two things.

First, he wanted to keep the number of books at twenty-four, in line with the popular understanding of the number of Old Testament books in the Western part of the Roman Empire. Second, he wanted to add these extra writings into the Old Testament canon. This is how he came up with the strange listing of the books.

This list begins to demonstrate how the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha were starting to achieve equal status with the canonical books.

Rufinius was a monk. He lived in such places as Egypt as well as on the Mount of Olives. He later returned to his birthplace in Italy where he became a presbyter, or elder in the church. He wrote a commentary on the Apostles’ Creed in which he listed the books of the Old Testament. His list numbered the sacred writings at twenty-two. None of the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha are listed in his canon. Rufinius does recognize three categories of religious books. Apart from the canonical are the ecclesiastical and the apocryphal books. Rufinius gives a list of the ecclesiastical books after he lists the Old Testament canon and the New Testament canon. These ecclesiastical works include Wisdom, Sirach, Tobit, Judith, and Maccabees. Rufinius clearly states, however, that these works were not to be used to establish doctrine.

What is interesting about Rufinius is that he comes up with his canon by understanding how the ancient Church fathers defined these books. It was not from the popular usage of the people. In other words, his canon was a result of careful investigation, not the popular view of the masses.

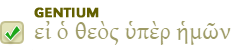

We now come to a major figure in the history of Bible translation, the learned scholar and Bible translator, Jerome. At this time in history, the church in the West read the Scriptures in Latin. However, there were many editions of the text. These various editions were known as the Old Latin. What was needed was a single edition. Thus, Jerome went about to update the Old Latin translation of the Bible.

Until the time of Jerome, the Latin Old Testament was translated from a translation; the Greek Old Testament or the Septuagint version. Instead of translating from a translation, Jerome wanted to translate the Old Testament from original sources, Hebrew and Aramaic. Jerome was one of the few scholars in the church who had learned Hebrew.

Because he wanted to translate from the Hebrew, he insisted on using the Hebrew canon as the basis of his translation. Consequently, he was very clear as to the number of sacred books that belonged in the Old Testament canon; there were only twenty-two. Like the Eastern Church Fathers, Jerome viewed the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha as outside of the canon. Furthermore, because of his knowledge of Hebrew, Jerome also rejected the additions that some have made to certain Old Testament books; the additions to Daniel and Esther as well as the letter of Jeremiah and the Book of Baruch.

As we have seen, with the exception of the Cheltenham List, every list of the Old Testament Scripture, from the time of Christ until the time of Jerome, has basically the same contents. The only books from the Old Testament Apocrypha that were part of any of these lists were the additions to the Hebrew text; such as the letter of Jeremiah and the Book of Baruch. As we have noted, they are added to the existing Old Testament; they are not accepted as stand-alone writings.

Consequently, like all the other individuals who investigated this subject, Jerome rejected the Old Testament Apocrypha as Holy Scripture. In fact, he did this in the strongest of terms. In the preface of his commentary on the Book of Daniel, Jerome wrote the following:

For all Scripture is by them divided into three parts, the Law, the Prophets, and the Hagiographa [the Holy Writings], which have respectively five, eight, and eleven books. (Jerome, Preface to the Book of Daniel)

Here again, we have the Old Testament books numbered at twenty-four. These twenty-four books correspond to the modern thirty-nine in the Protestant Old Testament ? they are merely divided differently.

Jerome actually left us with two canonical lists. Knowing that he would receive criticism for only using the Hebrew Scriptures, he listed the books of the Old Testament in the preface of his translation of Samuel and Kings. He entitled the preface, the “Helmeted Preface.” He used this title in anticipation of the criticism he was to receive for rejecting the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha. He did not believe the church had the right to determine the canon, rather the true canon was that which was given to the church and the world by the Jews; just as Paul had stated when he wrote to the Romans.

Jerome refused to place the Old Testament Apocrypha in his translation of the Old Testament because he realized that it was not part of Holy Scripture. These books could be read in the church for edification but not to establish doctrine.

It was only after the death of Jerome that the Old Testament Apocrypha was placed in the Latin Vulgate, which became the official translation of the Roman Catholic Church. His expert testimony was rejected.

Augustine of Hippo, a younger contemporary of Jerome, was probably the greatest theologian in the early church. He has provided us with his own list of the Old Testament canon. His list, however, was different from all of the earlier ones which have survived. Augustine listed the Old Testament canon at forty-four books; twice the traditional twenty-two. He individually listed each of the twelve Minor Prophets, divided Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles into two books, and separated Lamentations from Jeremiah, and Ezra from Nehemiah. Augustine also listed the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha as part of the Old Testament canon.

Why did he do this? Why did he include the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha? Why was his list so different than those who had come before him? The answer seems to be that the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha were widely read in the Western Church and had become popular with the people. Seemingly, the people made no distinction between them and the canonical books. Augustine did not seem to want to contradict the popular sentiment regarding the Old Testament Apocrypha, even though it was at odds with the historical view of the ancient Jews, the disciples of Jesus, and even Jesus Himself. Thus, Augustine merely accepted the current practices of the church with which he was familiar.

The fact that Augustine did not want to contradict the current usage among the people can be seen by a letter which he wrote to Jerome. He told Jerome that a riot almost broke out when the local bishop read Jerome’s translation of Jonah 4:6. In this verse, Jerome’s Latin translation rendered the plant that shaded Jonah as “ivy.” However, the people were used to hearing the Septuagint rendering of “gourd.” Augustine seemingly concluded that if a riot could occur with such a small change in a translation of one particular verse, what would the people do if they were told that certain entire books, which were read in the church, did not carry God’s authority?

Indeed, we find that on two occasions, Augustine wrote to Jerome and asked him to use the Septuagint as the basis of his new translation; not the Hebrew text. Thus, Augustine wanted to stay with the current practices of the church; no matter how contradictory it may have been to the historical evidence.

Augustine did more than merely side with the current attitudes among the churches. He insisted that the Western Church had the right to determine which books belonged in the Old Testament Scripture. According to Augustine, the canon was not closed until the church said it was closed. This is in spite of the fact that the ancient Jews, the apostles of Jesus, and Jesus Himself used a different canon!

However, Augustine was not in a position to make such an authoritative declaration about the contents of the Old Testament canon. For one thing, he had little contact with any of the church fathers in the East. This is unlike the other Latin Church Fathers who had investigated this issue and left us with a canonical list. In addition, Augustine was not a Hebrew scholar, as Jerome was, and neither was he an expert in this field of study. There is no evidence that he investigated this subject thoroughly, or that he took any notice of those who had preceded him. Indeed, we see this by noting the strange order in which he placed the Old Testament books. This listing was unique to him.

There is something else even more telling. Augustine knew that the Jews did not accept these apocryphal books as divinely inspired. Thus, he neglected, or rather rejected, the teaching of both testaments that it was the Jews who were entrusted with the oracles of God.

For example, the Old Testament says:

He proclaims his word to Jacob, his statutes and regulations to Israel. He has not done so with any other nation; they are not aware of his regulations. Praise the Lord! (Psalm 147:19-20 NET)

Notice it is only the nation Israel to whom God has proclaimed His regulations and statutes.

We find the same truth stated in the New Testament. The Apostle Paul wrote the following to the Romans:

Then what advantage has the Jew? Or what is the value of circumcision? Much, in every way. For in the first place the Jews were entrusted with the oracles of God. (Romans 3:1-2 NRSV)

Later, in the Book of Romans, we read:

For I could wish that I myself were accursed?cut off from Christ?for the sake of my people, my fellow countrymen who are Israelites. To them belong the adoption as sons, the glory, the covenants, the giving of the law, the temple worship, and the promises. To them belong the patriarchs, and from them, by human descent, came the Christ, who is God over all, blessed forever! Amen. (Romans 9:3-5 NET)

Paul says that the covenants, the giving of the Law, and the temple worship belong to the Jews; it was entrusted to them.

These passages of Scripture make this issue crystal clear. They state that it was the Jews who were entrusted with the oracles of God; not the church! Nowhere do we find Paul, or any other New Testament writer for that matter, saying that the Jews had violated this trust. We must also remember that Paul wrote this after the Jewish nation had rejected Jesus as the Messiah. Thus, the inspired apostle did not teach that the Jews had somehow lost their right to determine which writings constituted Old Testament Scripture.

Therefore, we must go to the Jews, and to them alone, to discover the exact extent of the canon. And what do we discover? We find that from every ancient written source that still exists, and speaks to this subject, that the extent of their canon of Scripture did not include the Old Testament Apocrypha!

This being the case, Augustine should have accepted the same canon which had been continuously held by the Jews from four centuries before the time of Christ until his day. Yet he rejected this canon. In its place, he added the Old Testament Apocrypha. He also insisted that the church had the right to determine the extent of the Old Testament canon in spite of the historical evidence, as well as the clear teaching of the Old and New Testament.

There is one last point about Augustine which needs to be addressed. So people argue that Augustine actually changed his mind about the authority of the Old Testament Apocrypha. In one of his writings, he seemed to have implied that the Old Testament Apocrypha did not have the same status as Holy Scripture. He wrote the following:

From this time, when the temple was rebuilt, down to the time of Aristobulus, the Jews had not kings but princes; and the reckoning of their dates is found, not in the Holy Scriptures which are called canonical, but in others, among which are also the books of the Maccabees. These are held as canonical, not by the Jews, but by the Church, on account of the extreme and wonderful sufferings of certain martyrs, who, before Christ had come in the flesh, contended for the law of God even unto death, and endured most grievous and horrible evils. (City of God 18.36)

There are several observations that we need to make from this passage. First, Augustine makes the distinction between the canon of the Jews and the canon of the church; he realizes that they are not the same. However, he says the church has the right to consider the books of the Maccabees as canonical because they contain accounts of believers being martyred for their faith.

Also, this passage could be read as saying that the books of the Maccabees are not Holy Scripture. At best, his testimony is ambiguous. As we have noted, he had no real expertise in this field. He did not know Hebrew, and neither was he a Greek scholar. This was not an area in which he excelled.

However, as we have seen, his expertise or non-expertise, is not the real issue; the issue is which canon did the ancient Jews and the New Testament writers accept as Holy Scripture?

There is something else we should note. Augustine mistakenly accepted the miraculous account of the origin of the Septuagint. He believed the translators were divinely inspired in the same manner as the biblical authors. An ancient account of its origin, known as the “Letter of Aristeas,” claimed that the seventy translators were put in separate rooms to translate the Law of Moses. When their seventy translations were compared, they were word-for-word the same! While at the time of Augustine it was popular to believe this account of the origin of the Septuagint, no one today takes this story seriously.

Though Augustine did not have the education, the background, or most importantly, the right to make such an authoritative declaration on the extent of the Old Testament Scripture, his word carried the day. Two church councils under his influence, the councils of Hippo and Carthage, declared the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha to be part of Holy Scripture. The Roman Church followed Augustine and included these writings as part of the Old Testament Scripture.

In doing so, the Roman Church rejected the idea that the Hebrew canon contained the only divinely inspired books from the Old Testament period. They also rejected the view of their own qualified translator, Jerome, as well as ignoring the biblical evidence that it was the Jews, and they alone, who had the responsibility to recognize which writings were to be placed into the Old Testament canon.

As we mentioned, two early church councils which accepted the Old Testament Apocrypha as authoritative Scripture were the councils of Hippo (393) and Carthage (397). After these councils declared the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha as part of Scripture, Pope Innocent I concurred with their decision in the year 405. Soon thereafter, in 419, the second Council of Carthage also approved the scriptural status of the Old Testament Apocrypha.

Yet, it was the council of Rome, which met in the year 392, which was actually the first council to approve the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha as canonical. Even though this was merely a local council, some Roman Catholics contend that their decision was authoritative for the entire church because it was sanctioned by an infallible source; Pope Damascus. Of course, this argument assumes that Damascus spoke with infallible authority.

On the other hand, not all Roman Catholic scholars agree that such affirmations by popes are infallible. Indeed, there are no infallible lists of infallible statements which were made by the popes! Any list that is produced would always have the same basic question asked about it; why should we consider this list infallible?

Indeed, we do not find any universally agreed upon criteria for accepting such lists of infallible statements by the various popes. In point of fact, Roman Catholic scholars admit that some popes erred in their teaching and were even guilty of heresy. Consequently, appealing to a certain pope to make an infallible statement about the ruling of a local council does not solve the issue of the extent of the Old Testament canon. Furthermore, we must remember that Protestants reject the idea that these early councils, or these popes, possessed any authority whatsoever to decide these matters.

Before moving on to our next historical era, we want to briefly sum up what we have learned from the testimony of the Eastern and Western Fathers of the fourth century and the beginning of the fifth century. In the East, the canon of Scripture was the canon of the Jews. While some of the Eastern Fathers thought that the Jews may have tampered with the text and omitted portions of Daniel, Esther, and Jeremiah, nowhere do we find them adding books to the Hebrew canon. From almost every source, we find the number of books listed at twenty-two. The only canonical book that was questioned was the Book of Esther. Thus, the Christian East was consistent in equating the canon of Scripture with the canon of the ancient Jews, Jesus, and His disciples.

However, in the West, the canon was not as well-defined. While Fathers like Rufinius and Jerome, who had investigated the issue, rejected the Old Testament Apocrypha as Scripture, some of these books were beginning to show up on certain lists. Augustine was the first church Father, in either the East or the West, who said that the decision as to the extent of the canon was the right of the church. In other words, no matter what the history of the canon among the Jews may have been, including the usage of the Lord Jesus and the apostles, the church, which was now some eight centuries removed from the composition of the last of the Old Testament books, had the right to determine its extent.

The councils of Rome, Hippo, and Carthage concurred with the position of Augustine and included the Old Testament Apocrypha with the Old Testament canon. The decisions of these councils was confirmed by Pope Damascus (for Rome), and Innocent I (for Hippo and Carthage). This basically settled the issue in the West for the next thousand years.

The view of Augustine about the Old Testament Apocrypha was also sanctioned in the late fifth and early sixth century by Pope Gelasius and Pope Hormisidas. Each of these men, in their position as Bishop of Rome, produced a list of canonical books which included the Old Testament Apocrypha.

During this historical period, we also find that a number of other Roman Catholic authorities, including Thomas Aquinas, concurred with this view of the Old Testament Apocrypha. Furthermore, they insisted that the church had the right to add these writings to the canon, though they were not accepted by the Jews, Jesus, or His apostles as Holy Scripture. Thus, for the next one thousand years, the church in the West read these Old Testament apocryphal books alongside the authoritative Scripture. They usually did this without making any distinction between them.

However, this is not to say that everyone during this period accepted these books as part of the Old Testament Scripture. To the contrary, there is evidence that the most learned scholars and church leaders of that era actually rejected the idea that these writings of the Old Testament Apocrypha were truly part of Holy Scripture. While we could cite a number of examples, we will mention only three.

One of the most important testimonies against the canonicity of the Old Testament Apocrypha comes from a pope, Gregory the Great. He served as pope from A.D. 590-604. In a commentary he wrote on the Book of Job, in which he completed in A.D. 595 in his fifth year as the pope, Gregory stated that the Apocryphal Book of First Maccabees was not canonical. Not only was his statement never rescinded, his work, Morals on Job, became the standard commentary on the Book of Job during the Middle Ages for the Western Church. While he may have been a private theologian when he began his commentary, he was the Bishop of Rome, or the pope, when he completed this work.

Thus, what we have here is a man who became the Bishop of Rome denying the canonicity of First Maccabees. This is after the council of Rome, the local council of Hippo and the provincial council of Carthage pronounced it, as well as the rest of the Old Testament Apocrypha, as Scripture. His words also contradict the earlier decrees by Pope Damascus and Pope Innocent I!

Which view is correct? Who has the authority to make such a decision? How is anyone to know for certain whom to believe?

This is not an isolated reference. Gregory’s view of the Old Testament Apocrypha reflected the opinion of many church leaders and theologians during the Middle Ages. The works, though called canonical, were not canonical in the sense that they were considered to be on par with Scripture. They could be read in the churches, but they were not to be used to establish doctrine.

The Glossa Ordinaria, or the “Ordinary Gloss,” was a compilation of glosses or comments which were made by the church Fathers about the Bible. It was the standard biblical commentary for the Western church in the Middle Ages. Indeed, this work was used in all theological centers during this period for the training of theologians.

In its preface, the Glossa Ordinaria states that the church permits the reading of the Old Testament Apocrypha, but only for devotion and instruction in manners; it is not to be read to establish doctrine or to resolve controversies. The Glossa Ordinaria repeats the statements of Jerome; there are only twenty-two books in the Old Testament and this does not include the Old Testament Apocrypha. This work consistently makes the distinction between the Old Testament Apocrypha and the canonical books. Since the Glossa Ordinaria was the official commentary on the Scripture for the Western Church in the Middle Ages, the statements which it makes concerning the Old Testament Apocrypha represent the consensus of the Church. This same view of the Old Testament Apocrypha was held by most of the learned theologians of the Middle Ages.

We will list one more testimony. On the eve of the Protestant Reformation, Cardinal Ximenes, the Archbishop of Toledo, made a distinction between the Old Testament Apocrypha and the canonical Old Testament in his massive work called the Complutensian Polyglot (1514-1517). We should note that this work was officially sanctioned by Pope Leo X, as well as being dedicated to him.

This work states in its preface that the books of Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, the Maccabees and the additions to Daniel and Esther are not canonical Scripture. The preface then went on to say that the Church does not use these books for confirming any fundamental points of doctrine. They are only to be read for the purpose of edification.

Consequently, this influential work shows that, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, there was still no consensus that these books of the Old Testament Apocrypha were authoritative Scripture. The fact that the pope officially sanctioned this work clearly demonstrates this point.

Thus, from these three examples, we find that there was no unanimity of opinion among the leaders of the Roman Catholic Church, the theologians, or even the popes, that the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha should be considered Holy Scripture. Even before the Protestant Reformation began, these writings were not considered canonical, or divinely authoritative, by all of the church authorities.

We now come to the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century. The Protestant Reformers, led by Martin Luther, advocated going back to the original sources to recognize the Old Testament canon of Scripture; the Hebrew Old Testament. In doing so, they rejected the canonicity of the Old Testament Apocrypha. Even as the Protestant Reformers were denying the divine status of the Old Testament Apocrypha, we discover certain Roman Catholic scholars doing the same thing.

Far from the matter of the status of the Old Testament Apocrypha as having been settled, noted Roman Catholic scholars during the beginning of the Protestant Reformation rejected these works as Scripture. One such scholar was Cardinal Cajetan. What makes his testimony all the more impressive is that he was the man who opposed Martin Luther at Augsburg. The evidence is as follows:

In 1532, the Cardinal published a work titled a Commentary on All the Authentic Historical Books of the Old Testament. His commentary, which he dedicated to the pope, did not include the Old Testament Apocrypha. If the Cardinal believed these writings were authentic Scripture, then they certainly would have been included in a book on “all the authentic” books of the Old Testament. However, he testifies that he sided with Jerome on this issue! The Old Testament Apocrypha was not canonical in the sense of being a rule of faith and practice, but rather these books were to be read in the church merely for edification. He put it this way:

Here we close our commentaries on the historical books of the Old Testament. For the rest (that is, Judith, Tobit, and the books of Maccabees) are counted by St. Jerome out of the canonical books, and are placed among the Apocrypha, along with Wisdom and Ecclesiasticus, as is plain from the Prologus Galeatus. Nor be thou disturbed, like a raw scholar, if thou shouldest find anywhere, either in the sacred councils or the sacred doctors, these books reckoned canonical. For the words as well as of councils as of doctors are to be reduced to the correction of Jerome. Now, according to his judgment, in the epistle to the bishops Chromatius and Heliodorus, these books (and any other like books in the canon of the bible) are not canonical, that is, not in the nature of a rule for confirming matters of faith. Yet, they may be called canonical, that is, in the nature of a rule for the edification of the faithful, as being received and authorised in the canon of the bible for that purpose. By the help of this distinction thou mayest see thy way clear through that which Augustine says, and what is written in the provincial council of Carthage’s (Commentary on All the Authentic Historical Books of the Old Testament. These are taken from his comments on the final chapter of Esther. Cited by William Whitaker, A Disputation on Holy Scripture (Cambridge: University Press, 1849), p. 48).

Notice the way he describes this issue. First, he says that these books are not canonical in the sense that they should not be used to confirm matters of faith. He then goes on to say that they can only be called canonical in a secondary sense of being edifying for the faithful, but not to establish doctrine.

Finally, he claims that this is the way Augustine, as well as the council of Carthage, understood the term canonical to mean when they described the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha. In other words, the term, “canonical” did not always mean divinely inspired or authoritative. Thus, when certain Roman Catholics had used this term to describe the Old Testament Apocrypha, they were using it in a general sense of a book that was helpful and edifying, but not necessarily authoritative! This is an incredible admission by a Roman Catholic cardinal.

We must also remember that this Roman Catholic scholar, who dedicated his work to the pope, wrote this a few short years before the council of Trent pronounced the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha as authoritative Scripture. The decision of Trent is in total contradiction to what he said was the historical view of the church!

We now come to the decree of the Council of Trent. While the councils of Rome (A.D. 392), Hippo (A.D. 393), and Carthage (A.D. 397) listed the Old Testament Apocrypha as canonical Scripture, their decisions were not binding upon the entire church. These councils had no universal authority among Roman Catholic believers. If these decisions of the councils had been universally considered to be binding, then the majority of theologians and scholars did not get the message. As we have already seen, there were written works from leading Roman Catholic sources, through the time of the Protestant Reformation, which did not include the Old Testament Apocrypha with the rest of the Old Testament Scripture. These councils seemingly settled nothing for the entire Roman Church.

It is only since the Council of Trent, which met from 1546 to 1563, that the Old Testament Apocrypha has had an authoritative status for the entire Roman Church. The fact that the Council of Trent settled the issue for Roman Catholics is admitted by the New Catholic Encyclopedia. It says:

St. Jerome distinguished between canonical books and ecclesiastical books. The latter he judged were circulated by the Church as good spiritual reading but were not recognized as authoritative Scripture. The situation remained unclear in the ensuing centuries... For example, John of Damascus, Gregory the Great, Walafrid, Nicolas of Lyra... continued to doubt the canonicity of the deuterocanonical books. According to Catholic doctrine, the proximate criterion of the biblical canon is the infallible decision of the Church. This decision was not given until rather late in the history of the Church at the Council of Trent. The Council of Trent definitively settled the matter of the Old Testament Canon. That this had not been done previously is apparent from the uncertainty that persisted up to the time of Trent. (New Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume II, The Bible, p. 390)

Unfortunately, the decision at Trent was made more than 1,900 years after the last book of the Old Testament was written. As we have discovered, it went against all of the biblical evidence, as well as all of the early historical evidence.

The Council of Trent established once-and-for-all the authority of the Old Testament Apocrypha for Roman Catholics. From the time of the decision made by Trent, until the present, the lines have been clearly drawn. The Roman Catholic Church accepts the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha as authoritative Scripture while the Protestant Church denies their divine authority. Either these books are part of Holy Scripture, as Roman Catholics and others contend, or, as the Protestants contend, they are mere human works in which no authoritative doctrines or practices can be discovered. There is no reconciling these two positions.

We would like to make a few further observations about the historical testimony which we have considered as well as some other historical issues dealing with the Old Testament Apocrypha.

One of the arguments often used in favor of the canonicity of the Old Testament Apocrypha is that many of the early church fathers quoted from these writings in the same manner as they were quoting Scripture. However, this is not really the case. When one closely examines the passages in the writings of the early church Fathers, which are supposed to establish the canonicity of the Old Testament Apocrypha, the evidence is not really there.

For one thing, some of the quotations are from additions or appendices to Daniel, Jeremiah or Esther. This is not the same as citing the Old Testament Apocrypha as Scripture. In citing the additions to these books, they were not adding further books to the Old Testament canon, they were accusing the Jews of omitting certain portions from the canonical writings. They were not accusing the Jews of deleting certain books from the canon.

There is something else to consider. Often the fathers cited these works, not as Scripture, but as writings which contained truth. Very few of the fathers, in actuality, give some sort of divine authority to the Old Testament Apocrypha. Therefore, the exact number of specific citations of the church fathers to the divine inspiration of the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha, is actually limited.

It is also worth noting that none of the church fathers that quoted the Old Testament Apocrypha as Scripture knew any Hebrew. Therefore, it seems they were not in a position to declare what was authoritative Scripture and what was not. Consequently, there is no vast number of citations of the Old Testament Apocrypha as Holy Scripture by the early church fathers.

The testimony of the early church Fathers is anything but uniform. While some of the Church Fathers, at times, cited the Old Testament Apocrypha, we also find that they do not restrict themselves to the books that now make up this collection of writings. Authors such as Justin, Tertullian, and Clement of Alexandria occasionally cite these books which are outside the present Old Testament Apocrypha - especially the Book of Enoch and First Esdras (also known as Third Esdras). Since these works are rejected as Scripture by Roman Catholics, what are we to make of these authorities citing them in this manner? Should we also consider these books as canonical?

Again, we must remember, that not every church Father who accepted the Old Testament Apocrypha as canonical had exactly the same list of books in mind. This adds to the problem as to what is the specific content of the Old Testament Apocrypha.

We can summarize it in this manner. Along with the acceptance of the traditional Old Testament, some early Fathers did not accept the Old Testament Apocrypha as Scripture, though they accepted these writings as helpful to the church. There were still others who not only accepted the Old Testament Apocrypha, in some sense, but they also accepted other additional books as well. The historical usage by the early church fathers is not consistent.

We must also remember that some people had a wider definition of the canon than the usual way the term is understood; as divinely inspired authoritative Scripture. To them, the canon did not merely contain the divinely inspired books, it also contained other books which were read in the church and were helpful for believers. This is the explanation that Cardinal Cajetan gave in clearing up the seemingly different views of Augustine and Jerome. According to the Cardinal, they were not contradicting one another. Augustine, when he said the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha were to be included in the canon, meant that these books could be read in the church along with the authoritative books. He did not mean that these books could be used to establish doctrine. The learned Cardinal also understood the Council of Carthage to mean the same thing when they added these books to the canon. Therefore, the word, “canon” was used in both a wide sense and in a narrow sense.

Some people argue that the existing manuscripts of the Septuagint translation prove that the Old Testament Apocrypha was part of the canon. They reckon that since these works were included in the Septuagint, they were considered to be Holy Scripture.

While we have briefly touched on this issue when we answered the previous question, it is helpful that we explain it here in a little more detail. The fact that some of the books from the Old Testament Apocrypha are found in early Greek manuscripts of the Bible is not as decisive as some people contend. These manuscripts also contain other written works that are neither part of the Scripture, nor part of the Old Testament Apocrypha ? everyone rejects them as having any divine authority.

Furthermore, in the three most important Greek manuscripts which contain some of these writings, the order and the contents of the books are always different. We can list them as follows:

Therefore, these existing manuscripts of the Septuagint are not uniform in their listing of the Old Testament Apocrypha. They either omit books accepted by the Roman Catholic Church or include books which are not part of the Old Testament Apocrypha.

For example, we find that Codex Vaticanus does not contain Second Maccabees or the Prayer of Manasseh. However, it does include Psalm 151 and 1 Esdras.

Codex Sinaiticus omits Second Maccabees and Baruch, but it includes Psalm 151, First Esdras and Fourth Maccabees.

Codex Alexandrinus includes Psalm 151, 1 Esdras, the Psalms of Solomon and Third and Fourth Maccabees.

Note that none of these Greek manuscripts contain all of the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha. In fact, only four (Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, and Ecclesiasticus) are found in all of them. Thus, no Greek manuscript has the exact list of Old Testament Apocryphal books accepted by the Council of Trent.

If someone points to the inclusion of the Old Testament Apocrypha among these early manuscripts as proof of their divine authority, then what do they do with these other works? Should they also be added to the Old Testament as well?

Therefore, these early Greek manuscripts are not a testimony to the canonical status of the Old Testament Apocrypha. However, we should recognize that all of the books of the Hebrew Old Testament were included in each of these manuscripts. Thus, the only conclusion we can make for certain from these manuscripts is that the traditional Old Testament books belonged in Holy Scripture. Nothing else.

As we mentioned in answering our previous question, the fact that certain books of the Old Testament Apocrypha were contained in Greek manuscripts of the 4th century A.D. does not prove they were part of the canon at the time of Christ. Thus, the early Greek manuscripts do not, in any way, give evidence of the divine status of the Old Testament Apocrypha.

As we have also noted, first-century Jewish writers, Josephus and Philo, used the Septuagint extensively. Yet, from their writings, we discover that they did not consider the Old Testament Apocrypha as a part of Holy Scripture.

One of the main problems with accepting the Old Testament Apocrypha as Holy Scripture is that it is not a well-defined unit. For example, the Latin Vulgate, which was the official translation of the Roman Catholic Church for over a thousand years, contains three books that are not part of the Old Testament or the Old Testament Apocrypha. They are First and Second Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh. Indeed, First and Second Esdras are found in most Latin manuscripts that contain the Old Testament.

In addition, these three works were placed with the Old Testament Apocrypha when the first edition of the King James Version was printed. This edition contained the Old Testament Apocrypha. The Eastern Orthodox Church, as well as the Russian Orthodox Church, do accept these three works as Scripture.

However, the Roman Catholic Church does not call these three books Scripture. Sometimes these three books are printed as an appendix to Roman Catholic Bibles after the New Testament. Sometimes they are omitted entirely. There is no consistency as how to treat these three writings. This adds to the confusion over the status of these books.

Some defenders of the Old Testament Apocrypha cite the Greek Orthodox Church, or Eastern Orthodox Church, as confirming their canonical status. However, the Greek Church has not always accepted the Old Testament Apocrypha as Holy Scripture. Actually, it has given conflicting positions. While these books were declared canonical by a number of different synods, Constantinople (1638), Jaffa (1642), and Jerusalem (1672), in 1839, their Larger Catechism omitted the Old Testament Apocrypha as part of Scripture. They did this on the basis that these books did not exist in the Hebrew Bible. Therefore, the Greek Church is not a consistent witness to the status of these writings.

Our survey has briefly summed up the use of the Old Testament Apocrypha by the church. From it, we noted why a number of additional books, and additions to books, eventually found their way into the Old Testament canon by certain Christians. We can sum this up as follows:

The first category consists of books whose authorship was mistaken. These writings were incorrectly assumed to be part of the original Hebrew canon, but were supposedly removed from the biblical books by the Jews. These include additions to Esther, Daniel, and Jeremiah. Believers in both the East and the West added these portions to the existing Old Testament. However, in doing this, they were not adding to the total number of Old Testament books, they were assuming they were restoring the original contents to these writings.

At times, other believers mistakenly assumed that the Book of Wisdom, and in some cases the Book of Sirach, was actually written by King Solomon. Consequently, they were added to the canon because it was thought that Solomon was the actual author. Again, we have an example of mistaken authorship.

Second, there were works which were recognized as not having been accepted as canonical by the Jews, but were considered as authoritative by the church. This includes Judith, Tobit, Wisdom, Sirach and First and Second Maccabees. Those who argued for their inclusion were not concerned about the identity of the human author of the book. Rather, their acceptance was based upon the authority of the church to make the ultimate decision on the issue. They claimed that it was the right of the church to include these works based upon its authority to make infallible decisions.

The Roman Catholic appeal to the testimony of history does not provide decisive evidence for the divine authority of the Old Testament Apocrypha. To the contrary, it provides no evidence whatsoever.

What the historical evidence does show is that from the beginning the church knew the extent of the Jewish canon; the same canon used by Christ and by His Apostles. Most leaders chose to accept it as the only divinely authoritative writings from the Old Testament period. Others, however, for totally inadequate reasons, added the Old Testament Apocrypha, merely human writings, to the divine canon of Scripture. This was a tragic mistake.

The Roman Catholic Church claims that the history of the church, in general, testifies to the authoritative status of the books which make up the Old Testament Apocrypha. These writings, along with the traditional books of the Hebrew canon, were supposedly continuously accepted as divinely authoritative by the leaders of the church. This is not true.

As we look at the evidence, we find that there are a number of early lists, which have come down to us, from both the East and the West. In these lists, the books of the Old Testament are specifically listed. What we learn from these lists is that there was a general consensus among Christians as to the extent of the Old Testament. It was the same as the Hebrew canon; twenty-two books. The only traditional book that was doubted was Esther.

In the East, certain additions were added to the existing books of Daniel, Esther, and Jeremiah by some of the Church Fathers. They did so mistakenly thinking that the Jews had deleted portions from these books. However, no stand-alone books were added to the Hebrew canon.

In the West, some of the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha began to show up on some of the lists in the fourth century. However, when Jerome translated the Old Testament Scripture into Latin, he ignored the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha as well as the additions to Daniel, Esther and Jeremiah. He realized these writings were not part of the Hebrew canon. He was criticized by some for not including these books which had become popular with the people.

The next major figure is Augustine. He produced a canonical list which contained the Old Testament Apocrypha, along with the universally recognized Old Testament books. Although he realized that the Jews did not recognize these books as Scripture, he believed the church had the right to add them to the canon. However, as we clearly saw from the Scripture, the right to determine the Old Testament canon belonged to the Jews and to them alone; not to the New Testament Church.

Nevertheless, the councils of Rome, Hippo, and Carthage agreed with the viewpoint of Augustine; the Old Testament Apocrypha was considered to be a part of the Old Testament canon. Two popes soon confirmed their decisions. For the Western church, the Old Testament Apocrypha was reckoned as part of the canon.

For the next one thousand years, the issue was not really debated. However, the great majority of learned scholars and theologians, like Jerome, made the distinction, between the Old Testament Apocrypha and the authoritative Old Testament writings.

During the Protestant Reformation, Luther and the reformers insisted that all doctrine must come from Scripture alone and this Scripture did not include the Old Testament Apocrypha.

In response to Luther, the council of Trent convened and resolved that the books of the Old Testament Apocrypha were to be considered as Holy Scripture. This is how the issue stands today: the Roman Church accepts these books as divinely authoritative, while Protestants reject the idea that they have any authority whatsoever.

The acceptance of the Old Testament Apocrypha seems to have been more of a concession to the popular usage of these works rather than to biblical and historical evidence.

As we noted, there are not any convincing reasons as to why these additions to biblical books, or complete books, should be included in Scripture. Indeed, leading Roman Catholic scholars, theologians, cardinals and even popes, until the council of Trent, rejected the divine authority of these ancient writings. If nothing else, this demonstrates that the historical view of the church toward these ancient writings does not give us any undisputed testimony to their divine character.

The Blue Letter Bible ministry and the BLB Institute hold to the historical, conservative Christian faith, which includes a firm belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. Since the text and audio content provided by BLB represent a range of evangelical traditions, all of the ideas and principles conveyed in the resource materials are not necessarily affirmed, in total, by this ministry.

Loading

Loading

| Interlinear |

| Bibles |

| Cross-Refs |

| Commentaries |

| Dictionaries |

| Miscellaneous |