Throughout the Hebrew Bible there are passages about a righteous servant who would suffer physical abuse, mockery, derision, rejection and finally death. This suffering servant, though pure from sin himself, is wounded on account of the sins of the people and through suffering and death, the people of God would be healed.[1] The identity of this suffering servant is, however, a serious point of controversy between Christian and Jewish scholars.

From the first days of the church, Christians have claimed that the suffering servant passages were references to the Messiah and that the rejection, suffering and death of Jesus of Nazareth were evidences for his Messiahship. Peter the Apostle points to the suffering and death of Jesus as a God ordained plan rather than an unforeseen consequence of a failed ministry;

Here Peter paraphrases Isaiah 53, one of the most famous of the suffering servant passages and declares its fulfillment in Jesus Christ.

Many Old Testament prophecies of a suffering, rejected individual are quoted in the New Testament as Messianic and fulfilled in the life of Jesus. The New Testament records that after his resurrection Jesus even declared that the Messiah must suffer:

Modern rabbis contend that the suffering servant is not the Messiah. Rather, they claim, he is either an unknown temple priest, perhaps King Hezekiah,[2] or even the nation of Israel itself.

Again, 20th century Jewish author Samuel Levine regarding the suffering servant in Isaiah 53:

However popular this belief has become in modern Jewish scholarship, it has not been held throughout the history of rabbinical thought. There is abundant written evidence, from ancient rabbinical sources, that the suffering servant is indeed the Messiah.[4] In fact, by the time of the writing of the Mishna and the Talmud, the paradoxical destiny of the Messiah had created a struggle in the minds of the rabbis. In addition to the suffering servant prophecies, the Bible had woven throughout its text the prophecies of a triumphant, ruling and reigning king who would bring everlasting righteousness to the earth and restore Israel to its place of prominence among the nations. This contradiction was too much for the rabbis to unite into one person. So, they began to speculate that there were to be two or possibly three Messiahs!

According to their speculations, the suffering servant, called Messiah Ben Joseph, would be killed in the war of Gog and Magog. The triumphant, ruling and reigning servant, called Messiah Ben David, would rebuild the temple and rule and reign in Jerusalem. This belief eventually became firmly rooted in the Talmud.[5]

There is great disagreement between Jewish and Christian scholars as to whether the suffering servant passages are indeed Messianic. From the Jewish perspective scholars argue, "If any people should have recognized the Messiah, the one who was the focus of their national existence, wouldn't it have been the Jews?" From the Christian perspective, others respond "But how could God have made the birth, lineage, character, mission and destiny of the Messiah any more obvious?"

Let's look at some of the suffering servant passages from the Hebrew Bible and their ancient interpretations to find the true identity of the one called the "suffering servant."

In the book of Isaiah there are a group passages called "The Suffering Servant Songs." These four vignettes are found in Isaiah 42:1-7, Isaiah 49:1-6, Isaiah 50:4-9, Isaiah 52:13-53:12. We will focus on the fourth suffering servant song since it is the most disputed portion of Isaiah.[6]

From the time of the development of the written Talmud (200 - 500 C.E.) this portion of scripture was believed to be Messianic. In fact, it was not until the 11th century C.E. that it was seriously proposed otherwise. At that time Rabbi Rashi began to interpret the suffering servant in these passages as reference to the nation of Israel.[7]

One of the oldest translations of the Hebrew scriptures are known as the Targums. These are aramaic translations of very ancient Hebrew manuscripts that also included commentary on the scriptures. They were translated in the first or second century B.C.E. In the Targum of Isaiah, we read this incredible quote regarding the suffering servant in Isaiah 53:

According to this commentary, the Messiah would suffer martyrdom, he would be, "The Righteous One" and would provide a way for God to forgive our sins. This forgiveness would be accomplished, not because of our goodness, but on account of the righteousness of Messiah. As we shall see, this is the very message of Jesus as recorded in the New Testament!

A reading from a Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah prayer book contains this passage:

In this beautiful prayer, a commentary on Isaiah 53, we discover several of the ancient beliefs on the mission of God's righteous Messiah:

1) He would apparently depart after an initial appearance: "Our righteous anointed is departed."

2) The Messiah would be the one who justifies the people:[11]

3) The Messiah would be wounded because of our transgressions and would take upon himself the yoke or punishment of our iniquities.[12]

4) By his wound we would be healed when he reappears as a "new creature."

In the Babylonian Talmud there are a number of commentaries on the suffering servant in Isaiah 53. In a discussion of the suffering inflicted upon this servant we find the following statement:

In another chapter of Sanhedrin we find a discussion on the name of the Messiah. In this remarkable portion of the Talmud we read:

In the Midrash we again find reference to the "Suffering Servant" of Isaiah 53. In characteristic fashion we read one Rabbi quoting another in a discussion of the Messiah's suffering:

In a portion of the Midrash, called the Haggadah (a portion which expounds on the non-legal parts of scripture) in the tractate Pesiqta Rabbati [Compiled in the ninth century, but based on writings from Talmudic times from 200 B.C.E.-400 C.E.] we read an interesting discussion of the suffering of the Messiah:

Another section of chapter 37, Pesiqta Rabbati, says the following:

In these fascinating portions of the Midrash we see language which closely parallels Psalm 22.[19] The writer specifically ties together the sufferings of the pierced servant in Psalm 22 (tongue shall cleave to your mouth...dried up like a potsherd) with the servant in Isaiah 53, whose sufferings provide a way for the children of Israel to be saved. The fact that the writer of this portion of the Midrash would tie the sufferings of the servant in Psalm 22 (the pierced one) and Isaiah 53, the despised and rejected one, is nothing less than astonishing. Clearly at least some of the rabbis of the ancient Midrashim believed that the Messiah would suffer and that the sufferings found in Psalm 22 and Isaiah 53 belong to the same person.

In the eleventh century C.E. the rabbinical interpretation of Isaiah 52-53 began to change. Rabbi Rashi, a well-respected member of the Midrashim, began to interpret this portion of scripture as a reference to the sufferings of the nation of Israel. However, even after this interpretation took root, there remained many dissenters who still held onto its original, Messianic view.

In the fourteenth century Rabbi Moshe Cohen Crispin, a strong adherent to the ancient opinion stated that applying the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 to the nation of Israel:

Rabbi Isaac Abrabanel (1437-1508), a member of the Midrashim, made the following remarkable declaration regarding the suffering servant of Isaiah 53:

Two centuries later we find the comments of another member of the Midrashim, Rabbi Elijah de Vidas, a Cabalistic scholar in 16th century. In his comments of Isaiah 53 we read:

We have also the writings of the 16th century Rabbi Moshe El Sheikh, who declares in his work "Commentaries of the Earlier Prophets," regarding the suffering servant in Isaiah 53:

These remarkable references from the ancient rabbis leave no doubt that the suffering servant in Isaiah 52:13-53:12 was indeed believed to be the Messiah. Even more remarkable is the fact that the suffering servant of Isaiah is connected with the suffering servant of Psalm 22. Finally, we find the ancient rabbis claiming that the suffering and death of the Messiah would have the effect of freeing us from our sins. This is in complete agreement with the Christian concept of the Messiah!

Even without these ancient references, there are several other reasons why the suffering servant in Isaiah 53 could not be the nation of Israel.

First, the suffering servant is an innocent person without sin:

Israel has an admittedly sinful past, the Hebrew scriptures even admit this fact. Psalm 14:2-3 says:

I Kings 8:46 says:

Ecclesiastes 7:20 says:

Secondly, the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 suffers on account of the sins of others.

Thirdly, the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 is willing to suffer.

In the entire history of their nation, the Jews have never suffered willingly.

Finally, the suffering servant's end was death.

The nation of Israel has suffered much, but she has never died. In fact, the nation of Israel was re-gathered back into the land after nearly 1900 years of world wide dispersion, an event unprecedented in world history.

Finally, listen to the words of 19th century Jewish scholar Herz Homberg;

Here we have in the clearest term possible the belief that the prophet was speaking of King Messiah. Furthermore, Homberg states that the Messiah, when he comes, will be rejected "as one of the vain fellows, believing none of the announcements which will be made by him in God's name." Finally, he sees the rejection and death of the Messiah accomplishing the role of the trespass-offering for the sins of the people. The Messiah suffers not because of the sins of himself, but on account of the sins of the people. Through Messiah's suffering and death "the promised redemption will eventually come!"

As we will see, in his understanding of Isaiah 53, Herzog has pointed out the very heart of the Christian message!

One of the most graphic and controversial portions of scripture is Psalm 22. The passage is disputed because of the nature of the sufferings it describes and because of the two different interpretations applied by Christian and Jewish Bible scholars. As we have already seen in the above discussion, the rabbis of the ancient Midrashim tied the sufferings of the Messiah figure in Isaiah 53 to those of the suffering servant of Psalm 22. However, today most modern rabbis deny the Messianic application of Psalm 22.

In these verses we find the rejection, mocking and death of a righteous servant of God, one "who trusted in the Lord" from the time of his birth, and did not despise the affliction he endured. Yet this Righteous One was a reproach to the people, a "worm," "scorned," one whose hands and feet were pierced and one so overcome with thirst that his tongue cleaved to his mouth.

The identity of this suffering servant is, to say the least, a point of great contention. The description of his physical suffering bears a striking resemblance to crucifixion, including the bleeding ("poured out like water"), the dehydration ("tongue cleaves to my mouth") and the disarticulation (dislocation of the joints) that occurs in crucifixion ("all my bones are out of joint"). Of course, Christians claim that this is a prophecy of the crucifixion of the Messiah, Jesus of Nazareth.

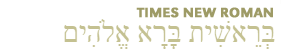

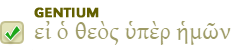

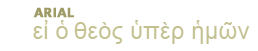

Perhaps the most controversial portion of the scripture is the interpretation of the word translated as "pierced." The most ancient translations of the Hebrew texts are the Greek Septuagint,[25] the Aramaic Targums [26]and Latin vulgate versions. These versions of the Bible were translated using very ancient Hebrew manuscripts that were extant in the period 400 B.C.E.-300 C.E. At that time the Hebrew language was diminishing in use, however it was still well understood by the ancient rabbis who translated the Tanakh. The seventy scholars that were chosen to translate the Hebrew manuscripts into Greek were certainly chosen because of their expertise in languages and understanding of scripture.[27]

When we examine these ancient translations of the Tanakh we find that in each case the word in question is translated from Hebrew into the Greek, Syriac or Latin word equivalent to "pierced." The ancient rabbis commissioned to translate the Tanakh into the Septuagint and the ancient Targums were apparently convinced that the word in question was indeed "pierced!" The fact that Christian translators (who translated the Hebrew Tanakh into the Latin vulgate) translated the same word as pierced, was not an issue at the time! They were simply following what the rabbis had done hundreds of years previously. However, since the "piercing" of Jesus of Nazareth, the translation of this word has become a major point of controversy.

Not only do most contemporary rabbis deny the Messianic application of this verse, some have even stated that Christians fabricated the translation themselves!

According to Samuel Levine:[28]

Mr. Levine is correct about one thing here. The ancient rabbis knew Hebrew perfectly well. But there is no doubt that the word translated as "pierced" was in their dictionaries because they rendered it that way in the Septuagint and the Targums! Both of these documents were translated some two hundred years before the birth of Jesus.

The Hebrew word which translates as "pierced" is the word "karv",  , and was certainly the word those ancient scholars translated. Modern Jewish Bibles translate the word in question as "like a lion." Obviously these are two very different meanings for what should be the same word in the biblical text. So where does this radical difference in rendering come from?

, and was certainly the word those ancient scholars translated. Modern Jewish Bibles translate the word in question as "like a lion." Obviously these are two very different meanings for what should be the same word in the biblical text. So where does this radical difference in rendering come from?

The Jewish Publication Society relies on the Massoretic Hebrew text for the translation of their version of the Bible.[29] However, this text is dated to approximately 800-1000 C.E. The writers of the Septuagint, the Targums and the early Christian Bibles relied on much more ancient texts.

The massoretic text has a completely different word, "kari"  (like a lion), instead of the word "karv"

(like a lion), instead of the word "karv"  (pierced) most likely found in the much more ancient texts.

(pierced) most likely found in the much more ancient texts.

Obviously when you look at the two Hebrew words,  and

and  , we see that they are structurally very similar. The Hebrew letter vav (

, we see that they are structurally very similar. The Hebrew letter vav ( ) found in "karv" (pierced) is very similar to the letter yod (

) found in "karv" (pierced) is very similar to the letter yod ( ) found in the word "kari" (like a lion). Clearly a mistake in copying was possible, but was this change from the ancient text a simple copyist' error or the deliberate changing of the text of the book of Psalms?

) found in the word "kari" (like a lion). Clearly a mistake in copying was possible, but was this change from the ancient text a simple copyist' error or the deliberate changing of the text of the book of Psalms?

Was the rejection of Jesus' Messianic claims by the first century rabbis the motive behind the changing of the text as well as its interpretation? We may never know.

Even without this dilemma we find that the ancient rabbinical interpretation of the word in question varies dramatically from modern rabbinical sources. The rabbis who wrote the Talmud and the Midrash interpreted this entire Psalm as Messianic.

In the Yakult Shimoni (#687), a commentary on Psalm 22 we read:

(karv) my hands and feet'. Rabbi Nehemiah says;'They pierced my hands and feet in the presence of Ahasuerus.'"

(karv) my hands and feet'. Rabbi Nehemiah says;'They pierced my hands and feet in the presence of Ahasuerus.'"

This commentary shows that the reading "pierced" was accepted by rabbis of that time.

Psalm 22 is also applied to the Messiah in the Midrash Pesikta Rabbati, (Piska chapter 36:1-2) as we saw in our discussion of Isaiah 52 & 53.

In the book of Zechariah we find a fascinating prophecy regarding the response of the nation of Israel when they are returned to their land and finally see and recognize their Messiah. God speaking through Zechariah stated:

Modern rabbis claim that the person spoken of here is not the Messiah, rather a king or priest of either the past or future. However, this very passage is applied to the suffering servant, Messiah Ben Joseph in the Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 52a. The rabbi asks:

In this amazing quote we see that the ancient rabbis believed that the Messiah would not only be "pierced" or "thrust through," but that he would also suffer martrydom ("the slaying of Messiah the son of Joseph").

Again we see how the interpretation of prophecy has changed over the last 1600 years. Was the piercing of the hands and feet of Jesus of Nazareth, and the thrusting through of his side by the Roman guard, the reason for the change of interpretation of these prophecies? If we are to argue that the ancient rabbis had a more thorough understanding of the ancient Hebrew language, we must accept the ancient views as closest to the true prophetic meaning.

The evidence speaks for itself. Throughout most of the history of Jewish scholarship many of the highly respected writers of the Talmud and the Midrash (most of whom were leaders of Rabbinical academies), shared a common belief. The Messiah would be despised, rejected, suffer by being pierced and ultimately die for the sins of the people!

Consequently, if the 20th century rabbi or Bible scholar chooses to cling to the belief that the Messiah will simply be a man who will not be despised, rejected or pierced, he will do so in stark contrast to ancient rabbinical thought and in the face of overwhelming and mounting evidence to the contrary.

Notes

[2] Babylonian Talmud, Sandedrin 98-99b.

[3] You Take Jesus, I'll Take God, Samuel Levine, pg 24-25 Hamoroh Press.1980.

[4] See appendix IV, Rabbinical Quotes on Isaiah 53.

[5] The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah, Alfred Edersheim, Appendix IX.

[6]. Messianically applied in Targum of Jonathan, written between first and second century C.E.

[7]. See The Messianic Hope, Arthur Kac.

[8] See comments on Isaiah 53 in Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah, Appendix IX.

[9] Yinon is one of the ancient rabbinical names of the Messiah.

[10] See The Messianic Hope, Arthur Kac, The Chapter of the Suffering Servent.

[11] To justify is to make one acceptable and righteous in the sight of God.

[12] i.e. Our individual sins.

[13] Talmud, Sanhedrin 93b.

[14] Talmud, Sanhedrin 98b.

[15] The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah, Alfred Edersheim, Appendix IX.

[16] A reference to Isaiah 53.

[17] A reference to the death of the Messiah

[18] A reference to Psalm 22:15-16

[19] In fact, there is no other portion of scripture that parallels the language in Presiqta Rabbati chapter 37 as closely as does Psalm 22.

[20] A Commentary of Rabbi Mosheh Kohen Ibn Crispin of Cordova. Fora detailed discussion of this reference see The Fifty Third Chapter of Isaiah According to Jewish Interpreters,preface pg x, S.R. Driver, A.D. Neubauer, KTAV Publishing House, Inc., New York, 1969.

[21] "The Messianic Hope", by Arthur Kac, pg. 75.

[22] ibid, pg. 76.

[23] ibid, pg. 76.

[24] From the exposition of the entire Old Testament, called Korem, by Herz Homberg (Wein, 1818).

[25] The Septuagint; seventy Hebrew and Greek scholars translated the Hebrew Tanakh into Greek beginning in 285 B.C.

[26] Targums: Translated in 200 B.C.

[27] Some Jewish legends say seventy-two scholars, six from each tribe of Israel, translated it in 285 B.C. The exact amount of time it took to translate the Tanakh (Genesis-Malachi) is not known. Some scholars feel that the Septuagint is flawed in some of its translations. However, it was accepted during the first century C.E.. as a bonafide translation and was used extensively in synagogues and by the common man.

[28] You Take Jesus, I'll Take God, Samuel Levine, pg. 34, Hamoroh Press, 1980.

[29] This is one of the major publishers of Bibles for the Conservative and Orthodox Jews.

The Blue Letter Bible ministry and the BLB Institute hold to the historical, conservative Christian faith, which includes a firm belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. Since the text and audio content provided by BLB represent a range of evangelical traditions, all of the ideas and principles conveyed in the resource materials are not necessarily affirmed, in total, by this ministry.

Loading

Loading

| Interlinear |

| Bibles |

| Cross-Refs |

| Commentaries |

| Dictionaries |

| Miscellaneous |