This lexicon was originally written by Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Gesenius (1786-1842) in the German language. Gesenius's influence as a master of Hebrew is widespread. The editors of the Brown-Driver-Briggs lexicon refer to him as the father of modern Hebrew Lexicography. Gesenius first published a work on Hebrew grammar in 1817 before turning his efforts on lexicography.

There have been various versions of Gesenius's work in English. We have chosen to use the version translated by Samuel P. Tregelles (1813-1875). Tregelles is most famous for his version of the Greek New Testament, though he also wrote hymns and worked with Hebrew grammar in addition to textual criticism.

As mentioned in the section called To the Student, Gesenius was a known rationalist, or neologian as Tregelles refers to him. Though some of these rationalistic expressions are found in the lexicon, Tregelles was faithful to make corrections, which are enclosed in brackets.

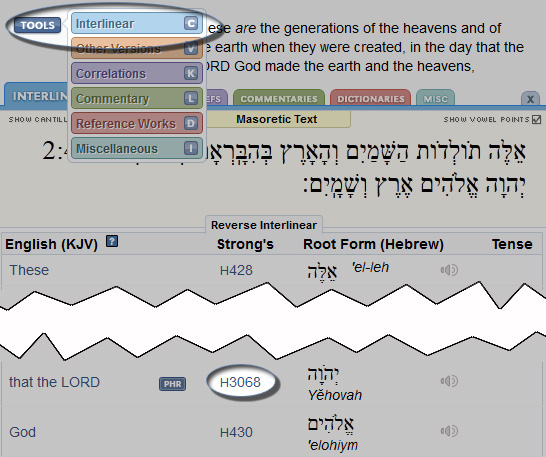

To get to the BLB lexicon pages, go to a verse, hover over Tools and click on Interlinear, then click on the appropriate Strong's number within the chart.

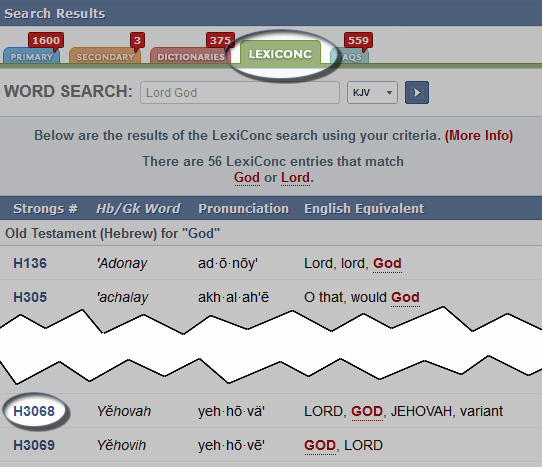

Another way to access the lexicon is through the LexiConc Tab. The LexiConc is a lexical concordance tool and searches the BLB lexicon for words which are used in the Authorized Version (please note: this does not search Gesenius's lexicon).

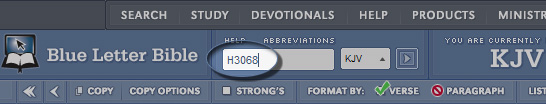

Or, if you are looking for a particular Strong's number, type it in the search box and hit enter:

Here are a few examples of important Hebrew words:

The following work is a translation of the "Lexicon Manuale Hebraicum et Chaldaicum in Veteris Testamenti Libros," of Dr. William Gesenius, late professor at Halle.

The attainments of Gesenius in Oriental literature are well known. This is not the place to dwell on them; it is more to our purpose to notice his lexicographical labours in the Hebrew language: this will inform the reader as to the original of the present work, and also what has been undertaken by the translator.

His first work in this department was the "Hebräisch-deutsches Handwörterbuch des Alten Testaments," 2 vols. 8vo., Leipzig, 1810—12.

Next appeared the "Neues Hebräisch-deutsches Handwörterbuch; ein für Schulen umgearbeiteter Auszug," etc., 8vo., Leipzig, 1815. Of this work a greatly-improved edition was published at Leipzig in 1823. Prefixed to it there is an Essay on the Sources of Hebrew Lexicography, to which Gesenius refers in others of his works. Another and yet further improved edition appeared in 1828.

In 1827, the printing commenced of a much more extensive work, his "Thesaurus Philologicus Criticus Linguæ Hebrææ et Chaldææ Veteris Testamenti." The first part of this work was published in 1829: the second part did not appear till 1835 (other philological labours, which will presently be noticed, having occupied a considerable portion of the intervening years). The third part of the "Thesaurus" appeared in 1839; a fourth in 1840; and a fifth in 1842; bringing the work down as far as the root  . On the 23rd of October, 1842, Gesenius died in his fifty-seventh year. His MSS., etc., were entrusted to his friend, Prof. Rödiger, in order to the completion of the work. Three years, however, have passed away without any further progress having been announced.1

. On the 23rd of October, 1842, Gesenius died in his fifty-seventh year. His MSS., etc., were entrusted to his friend, Prof. Rödiger, in order to the completion of the work. Three years, however, have passed away without any further progress having been announced.1

Between the publication of the first and second parts of the "Thesaurus," appeared the "Lexicon Manuale," in Latin, of which the present work is a translation; and also (in 1834), an edition of his German Lexicon, conformed to the "Lexicon Manuale."2

Of several of the above works translations have been made into English. In 1824, Josiah W. Gibbs, A.M., put forth a translation of the second of the afore-mentioned Lexicons, at Andover, in North America. This translation has also been twice reprinted in London.

The first of these Lexicons was translated by Christopher Leo, and published at Cambridge, in 2 vols. 4to., the former of which appeared in 1825.

In 1836 there was a translation published in America of the "Lexicon Manuale," by Edward Robinson, D.D.

This work of Dr. Robinson, as well as the translations of Gibbs, had become very scarce in England, and the want of a good "Hebrew and English Lexicon," really adapted to students, was felt by many.

The question arose, Whether a simple reprint of one of the existing translations would not sufficiently meet the want? It did not appear so to the present translator; and that on various grounds: Gibbs's work, having been based upon the earlier publications of Gesenius, was in a manner superseded by the author's later works; while, as regards the translation of Dr. Robinson, considerable difficulty was felt, owing to the manner in which the rationalist views, unhappily held by Gesenius, not only appeared in the work without correction, but also from the distinct statement of the translator's preface, that no remark was required on any theological views which the work might contain. Marks of evident haste and oversight were also very traceable through the work; and these considerations combined led to the present undertaking.

This translation was conducted on the following plan:—Each root was taken as it stands in the "Thesaurus," and the "Lexicon Manuale" was compared with it; such corrections or additions being made as seemed needful: the root and derivatives were at once translated, every Scripture reference being verified, and, when needful, corrected. A faithful adherence to this plan must insure, it is manifested, not only correctness in the work, but also much of the value of the "Thesaurus," in addition to the "Lexicon Manuale."

Every word has been further compared, and that carefully, with Professor Lee's Hebrew Lexicon; and when he questions statements made by Gesenius, the best authorities have been consulted. In Arabic roots, etc., Freytag's Lexicon has been used for verifying the statements of Gesenius which have been thus questioned. Winer's "Simonis" and other authorities were also compared.

In the situations and particulars of places mentioned in the Old Testament, many additions have been made from Robinson's "Biblical Researchers." The "Monumenta Phnicia" of Gesenius (which was published between the second and third parts of his "Thesaurus") has been used for the comparison of various subjects which it illustrates. It is a work of considerable importance to the Hebrew student; and it would be desirable that all the remains of the Phnician language therein contained be published separately, so as to exhibit all the genuine ancient Hebrew which exists besides that contained in the Old Testament.3 A few articles omitted by Gesenius have been added; these consist chiefly of proper names. The forms in which the proper names appear in the authorised English translation have been added throughout.

When this work was ready for the press, a second edition of Dr. Robinson's translation appeared: this is greatly superior to the first; and it has also, in the earlier parts, various additions and corrections from the MSS. of Gesenius. The publication of this new edition led the translator to question whether it would not be sufficient for the wants of the Hebrew student: a little examination, however, proved that it was liable to various objections, especially on the ground of its neology, scarcely a passage having been noted by Dr. Robinson as containing anything unsound. This was decisive: but further, the alterations and omissions are of a very arbitrary kind, and amount in several places to the whole or half of a column. It was thus apparent that the publication of the new American translation was in no sense a reason why this should be withheld. The translator has, however, availed himself of the advantage which that work afforded; his MS. has been carefully examined with it, and the additions, etc., of Gesenius have been cited from thence. This obligation to that work is thankfully and cheerfully acknowledged.4

It has been a special object with the translator, to note the interpretations of Gesenius which manifested neologian tendencies, in order that by a remark, or by querying a statement, the reader may be put on his guard. And if any passages should remain unmarked, in which doubt is cast upon Scripture inspiration, or in which the New and Old Testaments are spoken of as discrepant, or in which mistakes and ignorance are charged upon the "holy men of God who wrote as they were moved by the Holy Ghost,"—if any perchance remain in which these or any other neologian tendencies be left unnoticed—the translator wishes it distinctly to be understood that it is the effect of inadvertence alone, and not of design. This is a matter on which he feels it needful to be most explicit and decided.

The translator cannot dismiss this subject without the acknowledgment of his obligations to the Rev. Thomas Boys, M.A., for the material aid he has afforded him in those passages were the rationalism of Gesenius may be traced. For this, Mr. Boys was peculiarly adapted, from his long familiarity with Hebrew literature, especially with the works of Gesenius, both while engaged in Hebrew tuition, and whilst occupied in the Portuguese translation of the Scriptures.

All additions to the "Lexicon Manuale" have been enclosed between brackets []: those additions which are taken from the "Thesaurus," or any correction, etc., of the author, are marked with inverted commas also “ ”.

Nothing further seems necessary to add to the above remarks; they will inform the student as to the nature of the present work,—why it was undertaken,—and the mode in which it was executed. It has been the translator's especial desire and object that it might aid the student in acquiring a knowledge of the language in which God saw fit to give forth so large a portion of those "Holy Scriptures which are able to make wise unto salvation, through faith which is in Christ Jesus." To him be glory for ever and ever! Amen.

S. P. T.

ROME, February 24th, 1846.

The following are the more important MSS. which Gesenius consulted for his work, and which occasionally he cites:—

) by Abulwalid (

) by Abulwalid ( ) or Rabbi Jonah. This MS. is at Oxford. Uri. Catalog. Bibloth. Bodl. Nos. 456, 457.

) or Rabbi Jonah. This MS. is at Oxford. Uri. Catalog. Bibloth. Bodl. Nos. 456, 457.

1 The concluding part of the Thesaurus actually appeared in 1853: it completes the Roots in their alphabetical order; but the ample revision of the earlier part of that work which Gesenius had intended to publish, has not seen the light: his notes were probably often too rough and unfinished to be used with confidence: indeed it appears that Professor Rödiger, in completing the Thesaurus, had often rather to carry out the plan of Gesenius, than to use his fully prepared materials: it is well that so much was done by that distinguished scholar himself towards the completion of the work exhibiting his own matured views.

2 In 1847 the Lexicon Manuale was reprinted under the care of Professor A. T. Hoffmann of Jena.

3 The translator would here make a remark on the name Shemitic, which has been given by Gesenius and other scholars to that family of the languages to which Hebrew belongs.

This name has been justly objected to; for these languages were not peculiar to the race of Shem, nor yet co-extensive with them: the translator has ventured to adopt the term Phnicio-Shemitic, as implying the twofold character of the races who used these languages:—the Phnician branch of the race of Ham, as well as the Western division of the family of Shem.

This term, though only an approximation to accuracy, may be regarded as a qualification of the too general name Shemitic; and, in the present state of our knowledge, any approach to accuracy in nomenclature (where it does not interfere with well-known terms which custom has made familiar) will be found helpful to the student.

The following remark of Gesenius confirms the propriety of qualifying the too general term Shemitic by that of Phnician. He says of the Hebrew language—"So far as we can trace its history, Canaan was its home; it was essentially the language of the Canaanitish or Phnician race, by whom Palestine was inhabited before the immigration of Abraham's posterity."—Dr. B. Davies's translation of the last edition of Gesenius's Hebrew Grammar, by Prof. Rödiger, p. 6.

4 Other editions of Dr. Robinson's translation have since appeared: partly from stereotyped plates, and partly so printed as to admit of the introduction of Professor Rödiger's new arrangement and alterations.

In issuing a new impression of this translation of Gesenius's Lexicon, there are a few subjects to which I may with propriety advert.

The accurate study of the Old Testament in the original Hebrew, so far from becoming of less importance to Christian scholars than heretofore, is now far more necessary. For the attacks on Holy Scripture, as such, are far more frequently made through the Old Testament, and through difficulties or incongruities supposed to be found there, than was the case when this translation was executed. Indeed, in the eleven years which have elapsed since the final proof sheet of this Lexicon was transmitted to England, there has been new ground taken or revived amongst us in several important respects.

We now hear dogmatic assertions that certain passages of the Old Testament have been misunderstood—that they really contain sentiments and statements which cannot be correct,—which exhibit ignorance or the want of accurate and complete knowledge of truth on the part of the writers; and this we are told proves that all the inspiration which can be admitted, must be a very partial thing. We are indeed asked by some to accept fully the religious truth taught "in the Law, the Prophets, and the Psalms," while everything else may be (it is said) safely regarded as doubtful or unauthorised. It is affirmed that the Sacred writers received a certain commission, and that this commission was limited to that which is now defined to be religious truth: that is, that it was restricted to what some choose to consider may be exclusively thus regarded. To what an extent some have gone in limiting what they would own to be religious truth, is shown by their holding and teaching that we must judge how far the Apostles of our Lord were authorised in their applications of the Old Testament. Thus even in what is really religious truth of the most important kind, it is assumed that we are to be the judges of Scripture instead of receiving it, as taught by St. Paul, as "given by inspiration of God." We are farther told that it is incorrect, or only by a figure of speech, that we can predicate inspiration as attaching to the books themselves; that inspiration could only properly be ascribed to the writers; and thus the measure of the apprehension possessed by each writer, and the measure of his personal knowledge, is made to limit the truth taught in Scripture throughout. And these things are connected with such dogmatic assertions about the force of Hebrew words, and the meaning of Hebrew sentences, as will be found incapable of refutation on the part of him who is not acquainted with Hebrew, even though on other grounds he may be sure that fallacy exists somewhere.

Hence arises the peculiar importance mentioned above, of properly attending to Hebrew philology. A real acquaintance with that language, or even the ability of properly using the works of competent writers, will often show that the dogmatic assertion that something very peculiar must be the meaning of a Hebrew word or sentence, is only a petitio principii devised for the sake of certain deductions which are intended to be drawn. It may be seen by any competent scholar, not only that such strange signification is not necessary, but also that it is often inadmissible, unless we are allowed to resort to the most arbitrary conjectures.

Here, then, obsta priracipiis applies with full force: let the Hebrew language be known: let assertions be investigated, instead of assuming them to be correct, or of accepting them because of some famous scholar (or one who may profess to be such) who brings them forward. Thus will the Christian scholar be able to retort much of what is used against the authority of Holy Scripture upon the objectors themselves, and to show that on their principles anything almost might with equal certainty be affirmed respecting the force and bearing of any passage. And even in cases in which absolute certainty is hardly attainable, a knowledge of the Scripture in the original will enable the defender of God's truth to examine what is asserted, and it will hinder him from upholding right principles on insufficient grounds. Inaccurate scholarship has often detracted from the usefulness of the labours of those who have tried, and in great part successfully, to defend and uphold the authority of Scripture against objectors.

The mode in which some have introduced difficulties into the department of Hebrew Philology, has been by assigning new and strange meanings to Hebrew words,—by affirming that such meanings must be right in particular passages (although no where else), and by limiting the sense of a root or a term, so as to imply that some incorrectness of statement is found on the part of the Sacred writers.

Much of this has been introduced since the time of Gesenius, so that although he was unhappily not free from Neologian bias, others who have come after him have been far worse.

And this leads me to speak of one feature of this Lexicon as translated by me, to which some prominence may be given in considering these new questionings. This Lexicon in all respects is taken from Gesenius himself; all additions of every kind being carefully marked. The question is not whether others have improved upon Gesenius, but whether under his name they have or have not given his Lexicography. Students may rest assured that they have in this volume the Lexicography, arrangements, and divisions of Gesenius himself, and not of any who have sought to improve on him. For such things at least the translator is not answerable. It would be as just to blame a translator of a Dialogue of Plato for the manner and order in which the interlocutors appear, as a translator of Gesenius for not having deviated from his arrangements.

That Rationalistic tendencies should be pointed out, that such things should be noted and refuted. was only the proper course for any one to take who really receives the Old Testament as inspired by the Holy Ghost: so far from such additions being in any way a cause for regret, I still feel that had they not been introduced, I might have been doing an injury to revealed truth, and have increased that laxity of apprehension as to the authority of Holy Scripture, the prevalence of which I so much deplore.

That any should object to these anti-neologian remarks of mine is a cause of real sorrow to me; not on my own account, but on account of those whose sympathy with the sentiments on which I found it necessary to animadvert, is shown too plainly by what they have said on this subject. If they consider that an excessive fear of neology haunts my mind with morbid pressure, I will at least plainly avow that I still hold and maintain the sentiments expressed in my preface to this Lexicon eleven years ago: I receive Holy Scripture as being the Word of God, and I believe that on this, as well as on every other subject, we must bow to the sovereign authority of our Lord Jesus Christ, and of the Holy Ghost through the Apostles. Thus are we sufficiently taught how we should receive and use the Scriptures of the Old Testament as well as of the New. To be condemned with the writers of the New Testament, and for maintaining their authority in opposition to some newly devised philological canon for the interpretation of the Old, is a lot to which a Christian need but little object as to himself: he can only lament for those who thus condemn, and he must thus feel the need of warning others, lest they, too, should be misled.

Sound Hebrew Philology will, then, often hinder difficulties from being introduced into the text of Scripture, and will guard us against the supposition that the writers of the Old Testament introduced strange and incongruous things incompatible with true inspiration, and against the theory that the purport and hearing of Old Testament passages were misunderstood by the writers of the New.

Thus a whole class of supposed difficulties and objections is at once removed out of the way of him who receives Scripture as the record of the Holy Ghost: and though it is quite true that difficulties do remain, yet let it always be remembered that the principle laid down by discriminating writers, such as Henry Rogers,* remains untouched, that nothing is really an insuperable difficulty if it be capable of a solution: even if we do not see the true solution, yet if we can see what would suffice to meet the circumstances of the case, we may be satisfied that if all the particulars were known, every difficulty would vanish. And farther, it may be said, that if we receive the Old Testament Scriptures on the authority of our Lord and His Apostles as being really and truly the inspired revelation and record of the Holy Ghost, then all the supposed discrepancies must be only seeming, and we may use all that is written for our learning, whether history, precept, or prophecy, well assured that its authority is unaffected by any such difficulties.

Objections will no doubt continue to he raised: but he who uses Holy Scripture as that from which he has to learn the grace of Christ, the glory of His Person, the efficacy of His blood as the propitiation for sin, and the glories as yet unmanifested, which are secured in Him to all believers, will increasingly feel that he stands on a ground of security which can never be thus affected, He alone who is taught by the Spirit of God can know the true use and value of Holy Scripture. Hosea xiv. 9.

S. P. T.

Plymouth, Feb. 24, 1857.

* "The objector is always apt to take it for granted that the discrepancy is real; though it may be easy to suppose a case (and a possible case is quite sufficient for the purpose) which would neutralise the objection. Of this perverseness (we can call it by no other name) the examples are perpetual..... It may be objected, perhaps, that the gratuitous supposition of some unmentioned fact—which, if mentioned, would harmonise the apparently counter-statements of two historians—cannot be admitted, and is, in fact, a surrender of the argument. But to say so, is only to betray an utter ignorance of what the argument is. If an objection be founded on the alleged absolute contradiction of two statements, it is quite sufficient to show any (not the real but only a hypothetical and possible) medium of reconciling them; and the objection is in all fairness dissolved: and this would be felt by the honest logician, even if we did not know of any such instances in point of fact. We do know however of many." Reason and Faith, pp. 69—71.

The Blue Letter Bible ministry and the BLB Institute hold to the historical, conservative Christian faith, which includes a firm belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. Since the text and audio content provided by BLB represent a range of evangelical traditions, all of the ideas and principles conveyed in the resource materials are not necessarily affirmed, in total, by this ministry.

Loading

Loading

| Interlinear |

| Bibles |

| Cross-Refs |

| Commentaries |

| Dictionaries |

| Miscellaneous |