Interpretation:

in-tur-pre-ta'-shun:

1. General Principles:

Is a generic term and may refer to any work of literature. Referred specifically to the sacred Scriptures, the science of interpretation is generally known as hermeneutics, while the practical application of the principles of this science is exegesis. In nearly all cases, interpretation has in mind the thoughts of another, and then, further, these thoughts expressed in another language than that of the interpreter. In this sense it is used in Biblical research. A person has interpreted the thoughts of another when he has in his own mind a correct reproduction or photograph of the thought as it was conceived in the mind of the original writer or speaker. It is accordingly a purely reproductive process, involving no originality of thought on the part of the interpreter. If the latter adds anything of his own it is eisegesis and not exegesis. The moment the Bible student has in his own mind what was in the mind of the author or authors of the Biblical books when these were written, he has interpreted the thought of the Scriptures.

The interpretation of any specimen of literature will depend on the character of the work under consideration. A piece of poetry and a chapter of history will not be interpreted according to the same principles or rules. Particular rules that are legitimate in the explanation of a work of fiction would be entirely out of place in dealing with a record of facts. Accordingly, the rules of the correct interpretation of the Scriptures will depend upon the character of these writings themselves, and the principles which an interpreter will employ in his interpretation of the Scriptures will be in harmony with his ideas of what the Scriptures are as to origin, character, history, etc. In the nature of the case the dogmatical stand of the interpreter will materially influence his hermeneutics and exegesis. In the legitimate sense of the term, every interpreter of the Bible is "prejudiced," i.e. is guided by certain principles which he holds antecedently to his work of interpretation. If the modern advanced critic is right in maintaining that the Biblical books do not differ in kind or character from the religious books of other ancient peoples, such as the Indians or the Persians, then the same principles that he applies in the case of the Rig Veda or the Zend Avesta he will employ also in his exposition of the Scriptures. If, on the other hand, the Bible is for him a unique collection of writings, Divinely inspired and a revelation from the source of all truth, the Bible student will hesitate long before accepting contradictions, errors, mistakes, etc., in the Scriptures.

2. Special Principles:

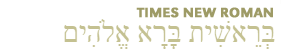

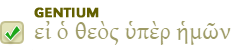

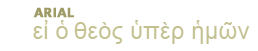

The Scriptures are a Divine and human product combined. That the holy men of God wrote as they were moved by the Spirit is the claim of the Scriptures themselves. Just where the line of demarcation is to be drawn between the human and the Divine factors in the production of the sacred Scriptures materially affects the principles of interpreting these writings (see INSPIRATION). That the human factor was sufficiently potent to shape the form of thought in the Scriptures is evident on all hands. Paul does not write as Peter does, nor John as James; the individuality of the writer of the different books appears not only in the style, choice of words, etc., but in the whole form of thought also. There are such things as a Pauline, a Johannine and a Petrine type of Christian thought, although there is only one body of Christian truth underlying all types. Insofar as the Bible is exactly like other books, it must be interpreted as we do other works of literature. The Scriptures are written in Hebrew and in Greek, and the principles of forms and of syntax that would apply to the explanation of other works written in these languages and under these circumstances must be applied to the Old Testament and New Testament also. Again, the Bible is written for men, and its thoughts are those of mankind and not of angels or creatures of a different or higher spiritual or intellectual character; and accordingly there is no specifically Biblical logic, or rhetoric, or grammar. The laws of thought and of the interpretation of thought in these matters pertain to the Bible as they do to other writings.

But in regard to the material contents of the Scriptures, matters are different and the principles of interpretation must be different. God is the author of the Scriptures which He has given through human agencies. Hence, the contents of the Scriptures, to a great extent, must be far above the ordinary concepts of the human mind. When John declares that God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son to redeem it, the interpreter does not do justice to the writer if he finds in the word "God" only the general philosophical #conception of the Deity and not that God who is our Father through Christ; for it was the latter thought that was in the mind of the writer when he penned these words. Thus, too, it is a false interpretation to find in "Our Father" anything but this specifically Biblical conception of God, nor is it possible for anybody but a believing Christian to utter this prayer (Mt 6:9) in the sense which Christ, who taught it to His disciples, intended.

Again, the example of Christ and His disciples in their treatment of the Old Testament teaches the principle that the ipse dixit of a Scriptural passage is to be interpreted as decisive as to its meaning. In the about 400 citations from the Old Testament found in the New Testament, there is not one in which the mere "It is written" is not regarded as settling its meaning. Whatever may be a Bible student's theory of inspiration, the teachings and the examples of interpretation found in the Scriptures are in perfect. harmony in this matter.

These latter facts, too, show that in the interpretation of the Scriptures principles must be applied that are not applicable in the explanation of other books. As God is the author of the Scriptures He may have had, and, as a matter of fact, in certain cases did have in mind more than the human agents through whom He spoke did themselves understand. The fact that, in the New Testament, persons like Aaron and David, institutions like the law, the sacrificial system, the priesthood and the like, are interpreted as typical of persons and things under the New Covenant shows that the true significance, e.g. of the Levitical system, can be found only when studied in the light of the New Testament fulfillment.

Again, the principle of parallelism, not for illustrative but for argumentative purposes, is a rule that can, in the nature of the case, be applied to the interpretation of the Scriptures alone and not elsewhere. As the Scriptures represent one body of truth, though in a kaleidoscopic variety of forms, a statement on a particular subject in one place can be accepted as in harmony with a statement on the same subject elsewhere. In short, in all of those characteristics in which the Scriptures are unlike other literary productions, the principles of interpretation of the Scriptures must also be unlike those employed in other cases.

3. Historical Data:

Owing chiefly to the dogmatical basis of hermeneutics as a science, there has been a great divergence of views in the history of the church as to the proper methods of interpretation. It is one of the characteristic and instructive features of the New Testament writers that they absolutely refrain from the allegorical method of interpretation current in those times, particularly in the writings of Philo. Not even Ga 4:22, correctly understood, is an exception, since this, if an allegorical interpretation at all, is an argumentum ad hominem. The sober and grammatical method of interpretation in the New Testament writers stands out, too, in bold and creditable contrast to that of the early Christian exegetes, even of Origen. Only the Syrian fathers seemed to be an exception to the fantasies of the allegorical methods. The Middle Ages produced nothing new in this sphere; but the Reformation, with its formal principle that the Bible and the Bible alone is the rule of faith and life, made the correct grammatical interpretation of the Scriptures practically a matter of necessity. In modern times, not at all prolific in scientific discussions of hermeneutical principles and practices, the exegetical methods of different interpreters are chiefly controlled by their views as to the origin and character of the Scriptural books, particularly in regard to their inspiration.

LITERATURE.

Terry, Biblical Hermeneutics, New York, 1884. Here the literature is fully given, as also in Weidner's Theological Encyclopedia, I, 266 ff.

Written by G. H. Schodde

The Blue Letter Bible ministry and the BLB Institute hold to the historical, conservative Christian faith, which includes a firm belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. Since the text and audio content provided by BLB represent a range of evangelical traditions, all of the ideas and principles conveyed in the resource materials are not necessarily affirmed, in total, by this ministry.

Loading

Loading

| Interlinear |

| Bibles |

| Cross-Refs |

| Commentaries |

| Dictionaries |

| Miscellaneous |